Goethe on the Four Stages of Culture

Goethe's Geistesepochen as applied to Classical and Western Culture.

First quarter of this article is freely available. To read the whole article, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Epochs of Human Spirit

In the oft-cited preface to The Decline of the West, Spengler names two individuals, Goethe and Nietzsche, to whom he remains firmly indebted. There, Spengler gives thanks to Goethe’s ‘method’ as found within his works on the natural sciences. But tucked away in a seemingly insignificant footnote in Volume II, Spengler demonstrates his admiration for Goethe again by referencing a rather obscure essay.

Goethe, in his little essay “Geistesepochen,” has characterized the four parts of a Culture—its preliminary, early, late, and civilized stages—with such a depth of insight that even today there is nothing to add. See the tables at the end of Vol. I, which agree with this exactly.1

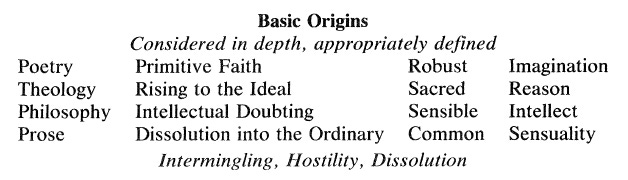

This remarkable essay, coming in at just under 500 words, is packed with profound insight and captures the conditions under which Spengler’s ‘Hochkulturen’ [High Cultures] develop. The essay itself was published in 1817 as an elaboration on Johann Gottfried Hermann’s dissertation on ancient mythology. But what sticks out is its remarkable anticipation of Spengler’s ideas. Here, Goethe traces the archetypal development of Culture as it moves across four stages: the Poetic, the Theological, the Philosophical, and the Prosaic. Man’s mind originates in a primitive mysticism, rises to an intellectual maturity, and crashes back into a dark age from which it began. Each stage along this development is characterized by a different theme and whose major productions reflect as much. Poetic cosmogonies are wedded to theologies by scholastics, scholastics pave the way for philosophers, and the intellectual doubting of a Socrates-like figure leads to the intellectual sterilization of a vulgar and now ‘civilized’ Culture.

Though there may be “nothing to add”, I hope that drawing attention to the historical particulars of Goethe’s somewhat abstract essay will still be illuminating. What follows is a brief history of two Cultures (The Greco-Roman Classical, and the more recent Western European) and their respective ‘Spiritual’ developments.

The Poetic

As described by Goethe:

The primeval phase of the world, of nations, of individual human beings is the same. At first everything is enveloped by a desolate void, but the spirit already contemplates the creation of the animate and inanimate world. While the primitive masses look about with fear and amazement in search of the barest necessities, a more advanced spirit gazes at the great phenomena of the world, perceives what occurs there, and gives utterance to what exists with profound awareness as if it came into being before his very eyes. Therefore, in the earliest stage we have the contemplation and the philosophy of nature, the defining and the poetry of nature—all in one.

The world gets brighter, and the obscure elements become clearer and take on outline. Man reaches out in order to gain mastery of them in a different way. This new man surveys the world with a simple, healthy sensuousness which sees nothing but itself reflected in things past and present. He gives new shape to old names, anthropomorphizes and personifies things, and beings living and dead, and imparts his own character to all creatures. Thus primitive faith lives and thrives, and, often recklessly, rids itself of all abstruse remnants from the primeval epoch. Poetry flourishes, and only he who has innate primitive faith or can acquire it, is a poet. This epoch is characterized by a free, robust, serious, noble sensuousness, which is elevated through the power of the imagination.

Just as a man who awakes in the morning is still half-asleep, a freshly awoken Culture is still steeped in a dream-like haze. His imagination is populated with images of gods, spirits, and heroes. Legends and fairytales are treated with sincerity and become the basis for great works of poetry.

For the Greeks, this poetic period is best represented by the works of Homer. One finds descriptions of legendary events, battles, gods, and creatures. Diomedes confronts Ares, Achilles is the son of a sea nymph, Aeneas is whisked away from battle by his mother, Aphrodite. The Greek gods are not yet theological abstractions but are instead bursting with personality and idiosyncrasy. At this stage of man’s mind, these are plainly accepted. Magic, mythical creatures, gods, enchanted armaments, and fate were once the norm.

The same goes for the West, which Spengler separates from Greco-Roman Culture and argues began around the year 900 AD. The cultural cycle begins anew and homologous poetic works emerge. The Norse Poetic Edda and German Nibelungenlied operate on the same mythical consciousness structure that Homer’s works once had. Conspiring gods, fates, curses, and enchanted objects make their mark on the affairs of men. Perhaps the most culturally enduring works of the West’s poetic stage were the Arthurian legends and the quest for the Holy Grail. In the story of Percival’s quest for the Grail, we see a divine mission, chivalric warriors, and enchanted objects presented just as they were in Homer. A naïve and robust imagination that embraces legend without attempts at rationalization.

The Theological

As described by Goethe:

But since man knows no limit in his pursuit of self-improvement and because the enlightened aspect of existence is not always to his liking, he longs to return to mystical experience and searches for a higher power behind the world of appearances. And just as poetry creates dryads and hamadryads and makes them subjects of higher gods, so theology creates a hierarchy of demons that are envisioned to be ultimately dependent on one god. We may call this time the sacred epoch. Although it is essentially a product of reason, the rational spirit gradually loses its influence. Primitive faith is reclaimed, modified to suit the time, and the miraculous is proclaimed to have objective rather than poetic validity. To this the intelligent mind must object, although in its ideal state and form it worships the primitive beginnings, takes pleasure in the poetic primitive faith, and values the noble human need to accept a supreme being.

Theology, the queen of the sciences, is humanity’s earliest attempts at cognizing their world as a rational ordering of the cosmos. We see it at work first in cosmogonic poetries of a Dante or a Hesiod. It brings order to the cosmological soup that Poetic mankind first concocted. Mythological beings are given genealogies to assert some logical connection between symbols. Though convoluted at times, we can see how the Greeks made associations between Gods which represented different aspects of existence—how Nyx, the goddess of night gave birth to Thanatos [Death] and Nemesis [Retribution] and so on.