A Revolution in Cartography

Spengler's "Plan for a New Atlas of Antiquity" in English for the first time!

I’ve decided to move forward with translating Spengler. This time, I present to you Spengler’s Plan eines neuen Atlas Antiquus. As I mentioned in the last post, Spengler gave a presentation to the German Oriental Society in October of 1924. Altasien, yesterday’s subject, was written down after this lecture as an outline to a book where Spengler intended on putting some of these ideas into practice.

Here, he pleads with German scholars to rethink the use of cartography in their study of prehistory. Though the lecture is charming in its own right, (who wouldn’t want to listen to Spengler sperg out over maps?) I think Spengler is making an important methodological point here. Spengler’s unique approach to the study of history is firmly rooted in Romantic conceptions of Natural Science (namely, Goethe’s botanical and morphological researches). This entails entering a teleological communion of sorts with the object of inquiry. In order for you to truly ascertain a Culture’s morphology, you must allow it to impress itself upon your mind’s eye. This way, you can reconstruct its form and animating principles within your mind—whether this yields a heuristic image or the true “spirit” of the organism is still up for discussion. But regardless, actually seeing the entity and seeing its development over time is paramount to this synthetic activity. Thus, Spengler has a very strong interest in insisting upon better maps to aid his unique style of research.

A quick note on the translation: Spengler makes repeated reference to Kartenbild. This would literally translate to something like, “map-image” or “map-picture”. But I think Spengler is pointing to something deeper (and I have no knowledge of German cartographic scholarship to suggest anything to the contrary). Perhaps he is referring to the way our maps can literally structure the image of World-History within the mind’s eye. Or perhaps he means to convey maps as a type of higher-order visual depiction of historical information. Whatever the case may be, I’ve left the word untranslated where seemingly appropriate.

And lastly, consider becoming a paid subscriber to The Oswald Spengler Project! Paid subscriptions allow me to put more time and effort into these posts. A measly $5 ensures more posts on Spengler, history, and culture.

Plan for a New Atlas of Antiquity

By Oswald Spengler

The following draft is not intended to represent anything definitive or perfect, but rather to be presented for discussion in scholarly circles. Apart from the scholarly feasibility, which I already consider to be assured after the first impressions, the plan also has a very serious technical and economic aspect, which will not be discussed here.

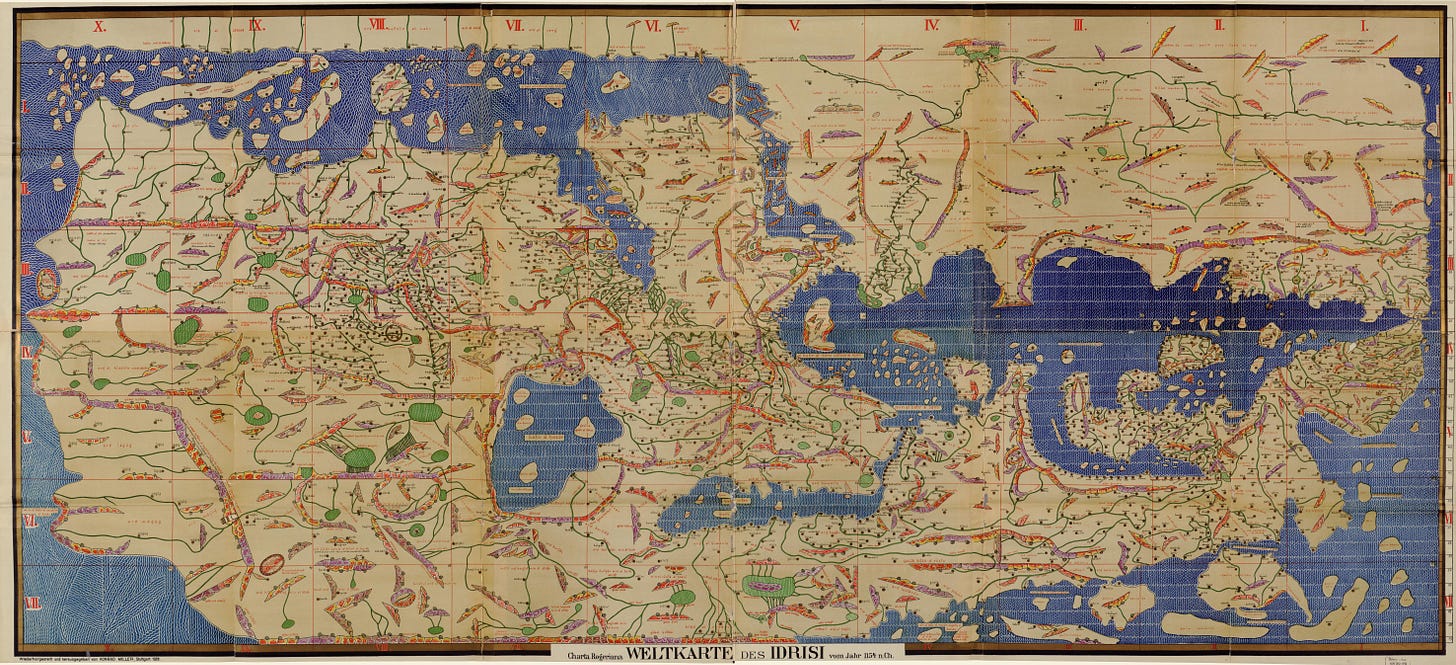

Since historical geography in Germany and elsewhere has all but died out, a state of emergency has developed within historical research, along with its consequences, which we hardly recognize. The result of all historical research is a historical picture which can be presented in cartographic form according to certain ideas for the eye. As a rule, the map refrains from the personal and unique, but it brings out the general form all the more sharply and thus makes it possible to see and feel together at a single glance in a way that no report, however clearly written, can. The extent to which this is the case depends significantly on the cartographic technique, which has its foundations, ideas, and ingenious insights, just like any other technique.

It is now a fact that these maps that accompany our historical research have remained almost unchanged in fact and form for 50 years. In older areas such as Greek or Roman history, the map, as usually attached to a book, is two generations behind the state of research. For the more recent areas (Indian, Chinese, pre-Homeric, Neo-Persian history, etc.) there is no corresponding map at all. For the Aegean world we still have nothing better than the map that treats the borders of Greek dialects as political borders, that is, from a time when ancient history was a secondary task of classical philology. Excavations, tomb explorations, and comparative ceramics have left no trace of this image. The delineation of these maps is outdated, the drawings are outdated, the names are outdated.

We have long been accustomed to reading learned works about the Etruscans, the Hittites, and predynastic Egypt, without knowing how the mentioned places and names relate to each other spatially. It happens that books of this kind become almost incomprehensible to the majority of readers; that they contain old-style maps on which the things mentioned do not appear at all, or hand-drawn sketches in which the eye cannot find its way. It happens daily that the author himself falls into a litany of errors and misconceptions by combining historical facts without being geographically “in the picture”, or that he fails to notice decisive connections. One must calculate how many areas of today’s historical research we lack a technically elaborated map: for India during the Vedic period, for the Homeric period, for Italy at the time of Rome’s founding, for the oldest age of Egypt and Babylon, for the spread of religions and cults of the Roman imperial era. I consider it one of the most urgent tasks of German scholarship to create a new Kartenbild [map image] based on the comprehensive results of scholarly research over the last 50 years, which gives equal expression to the historical.

But this image must be designed according to completely different principles. We need new ideas in cartography because we have gained a new perspective on the course and meaning of history. In the last century, it was enough to draw rivers, cities, political borders, and the names of people on a map. Today we need—within the limits of what is possible—first of all a representation of the terrain, insofar as it promoted or hindered agriculture, settlement, and transportation at that time; in addition to irrigation and the altitude layers, sometimes the stratification of the soil, the occurrence of metals and rare rocks; the sea currents and wind directions, which guided early maritime traffic and thus also the flows of people in certain directions. Furthermore, if possible, an indication of the plant life during the individual historical periods. The vast forest masses are the only decisive obstacle to travel and migration in early times. “Plain” means “clearing” in the Nordic languages. The sea has always connected the early Cultures and populations; the primeval forest separated them. It is also a necessary prerequisite for the historical Kartenbild that the drying up of ever larger areas following the Nordic Ice Age and the subsequent forest and swamp period from the south is also made the basis of the political image. As the rock carvings demonstrate, the Sahara scarcely emerged before the 4th millennium. It was not until Roman times that it broke into Mauritania. In those days, Spain was the land of impenetrable forests. A millennium later, the Moors were only able to halt desertification through artificial irrigation. But the same applies to Arabia, Babylonia, and Inner Asia. The prehistory of the two oldest Cultures did not yet take place under the influence of the isolation of their respective river valleys. But without understanding this, one cannot understand political prehistory. Egypt originally had no natural western boundary in the desert.

The Kartenbild also includes the most important results of zoogeography1: the respective distribution of horses, cattle, and lions. An attempt has recently been made to determine the ancient migrations of the Hamites from the distribution of African cattle breeds. In addition, the proper recording of archaeological finds is essential: the types of graves, the shapes of pottery, the types of settlements, the treatment of bronze. Without this, a map of ancient Italy is worthless today. As long as only the Etruscans are mentioned and one cannot grasp the distribution of so-called Etruscan cities by age and location, as well as their layers of graves at a glance, the Etruscan question will not make sense at all. The map is the only means of presenting to the researcher in a single field the results of all other sciences, as far as they concern him, in a useful and meaningful order.

Then the Rassenfrage [race-question]! It is no longer sufficient to simply print the common ethnic names from very different historical periods over and next to each other. A map, of ancient Italy or Anatolia for example, must contain, in addition to the distribution of languages and dialects, an indication of the of the type of people (height, build, skull shape, facial structures), which never coincides with language boundaries, and only then, and independently of this, the historical ethnic names, indicating their ongoing shifts, substitutions, and superimpositions. This is already possible today in many cases with great accuracy, especially as it is one of the most important findings of the latest racial research that many physical characteristics adhere to a country with great tenacity and have repeatedly asserted themselves despite all migrations since the Stone Age.

It is clear that maps of this style can only be produced by a collaboration of representatives from diverse disciplines. A single person is no longer up to the task. But if the geologist, the animal-geographer, and plant-geographer first create a foundation, in which the anthropologist and prehistorian make their entries, in order to finally make room for the representative of political and economic history, it is conceivable that visual material will lead to discoveries for the eye by its mere presence, which would have remained closed to pure book work. Something like this is only possible in Germany today. No other country in the world possesses such well-rounded scholarship and such a maturity of methods as must be assumed here. If internal or external reasons thwart the plan in Germany, it will never and nowhere be realized. And finally, historical research will falter due to the obstacle placed in its way by the lack of geographical foundation. The only factual objection is that research does not yet allow a conclusive picture to be drawn. But this conclusion will never be reached; the picture changes from one generation to the next; and if the preliminary picture is not sketched because of the necessary gaps, a more mature one will not be at all possible.

The scope of such a work is to be measured quite differently than 50 years ago. The primitive cultures encompass the entire earth, they have used all the seas along the coasts and island chains as go-betweens and form, with their spheres and currents a living whole, without which one is not able to survey the origin and prior history of the High Cultures. Today it is no longer possible to find an eastern boundary for the so-called science of antiquity. Questions of the Homeric era extend as far as the Baltic Sea and the Niger River; the world of forms of migration of peoples cannot be understood without the historical image of Inner Asia and even China; the Stone Age of the northern edges of the Indian Ocean belongs to Egypt and Babylon. On the other hand, the upward historical boundary can easily be identified in the Crusades and the Mongol invasion. From then on, the historical Kartenbild has a different meaning, not internally, but for our practical purposes, and the selection and methodology of what is to be represented have a different tendency. Under this assumption, a natural grouping of the map-material emerges as follows:

A group of maps of the primitive world, covering its entire extent across all parts of the world, with an overview of the myriad of archaeological finds, metal sites, and transportation routes of ancient commerce and subsequent migrations, with the distribution of basic religious, social, economic, and political forms. Such a map would simplify and solve a whole series of problems in the study of early history. Individual adventurers, for example, can go wherever they want, but entire tribes always follow a known route that is secured by local inhabitants in terms of food and loot. It, therefore, can also be determined geographically from the local ecology and the type of settlement.

A joint group would need to address the destines of Egypt and Babylonia along with their surrounding world, starting from the earliest times of stone workings and the Sahara, still then covered by vegetation, and ending around the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Here, need an overview of the ethnographic divisions, the districts of Egypt, the Sumerian principalities, the geographical distribution of cults and gods, the shift in the political focus over the course of time, and the deep connections from the Indian Ocean deep into the northern landmass.

The Near Eastern world between Cyrene and Iran, the Black Sea and southern Arabia, from 1500 to the Persian period. This is where the great flows of peoples from the vast inland regions of the north came from, which fundamentally altered the landscape both materially and spiritually. Today, we have the results of the excavations of B? And Amarna, Troy and ancient Italy, those of comparative name research, the cuneiform and hieroglyphic literature, but we have nothing that could be called a representation of these results in map form [Kartenbilde]. And it is precisely here that we are groping in the dark for lack of a visual synthesis, passing by obvious discoveries and permitting errors to grow and flourish. Errors that the first best Kartenbilde of this sort would have stamped out from the beginning.

The Indian world. Here, decisive discoveries are soon to be expected once the results of purely literary research are combined with our rapidly growing archaeological findings. The distribution and stratification of the graves, weapons, and vessel forms [ceramics] must, as soon as they are available to the Indologist, change the entire structure of Indian history. Thereby giving an idea of the Dravidian culture and illuminating the destiny of the ancient Aryan world. However, I am not aware of the existence of such a map of ancient India.

Recently in the study of ancient Chinese culture, several attempts have been made to geographically define the earliest organization of states along the Yellow River based on historical sources. If this had been done earlier, the concept of ancient China would still not be emotionally equated with the country that now bears its name (thus casting this entire history in a false light). The world of states in the early Zhou dynasty was as small and complex as that of the Homeric period. All these statelets could be squeezed into an area the size of southern Germany, and the principalities of the earliest Vedic period were certainly not much larger.

A cartographic survey of the two ancient American Cultures [Mesoamerican and Incan], for which the first inadequate attempts already exist.

Now, the vorantike [pre-antique2] world of the entire Mediterranean in the 2nd millennium, i.e. down to Homer, with paths of the Sea Peoples who advanced towards Egypt in the 14th and 13th centuries, with the circles and strata of the Iberian, partly originating deep in Africa, the Sardinian, Etruscan, Libyan, Minoan, and Mycenaean form-worlds. The connections extend to the rock paintings of Scandinavia and the findings in the Sudan, Nubia, and southern Arabia. These are the preconditions for the later structure of the antiken Welt [World of Greco-Roman Antiquity], which until now has been reconstructed backwards from the written sources and thus, initially, philologically.

Now, the antike Welt itself, until the migration of peoples, and its geographical image must be completely redrawn. We must finally see how not only the physical characteristics, but also its destiny and political significance shift, how certain main areas of Homeric culture—Thessaly, for example—receded, while others—like Latium—rise to prominence, how important towns became villages and how villages became cities. We must finally—and not only here!—make discernible the deep inner difference between castle, settlement, market, town, trading post, provincial, metropolitan, and cosmopolitan city. Between tribe, ethnicity, nation. Between landscape, region, and state. All must be made visually discernible. The Etruscan name, as well as the names Hellene, Roman, Ionian, and Italic designate something different in each century. The age of formation of cities around 800 BC and that of the dissolution of the city-states into great powers around 300 BC must be depicted with an eye toward their development, as well as the racial relations down to the imperial period, where the population of the individual provinces is still simply designated today by their names instead of dialect, adoption or rejection of certain cults, disappearance or increase of the rural population, accumulation or reduction of medium-sized cities. It can be seen to a large extent where the valley regions have a different type of people than the highlands, where the pre-Indo-Germanic population remained in masses. Only this again explains the movement of the Germanic tribes: where they settle en masse and displace the natives, where they sit only as landlords over a class of serfs, where they exercise formal rule. Only when one sees this does one understand the formation of new nations and their languages, the long duration or the rapid collapse of Germanic domains—the Gothic rule in Italy did not take root because there was a lack of wide river valleys south of the Apennines, while the Visigothic Kingdom in Spain sat on the plateau as if on a fortress.

The darkest area of history as well as geography is the Near East from Alexander the Great to the Mongol conquests. We possess nothing that gives us a clear picture of Byzantium, such as the linguistic, social, and religious stratification of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt under the rule of Justinian; the Sassanid Empire, a most decisive creation at the crossroads of four High Cultures, is still a formless concept to us today. Apart from the spread of Christianity on the soil of the Roman Empire, we do not even have an attempt to trace the spread of the then new religions from the time after Christ’s birth, the Jewish-Talmudic, Zoroastrian, Manichaean, later the Nestorian, the spread of the so-called cults of Sol and Mithras in late antiquity to as far as Portugal and Inner Asia. We do not see in the map how these religious communities became nations and which disintegrated the older states; how these nations partly had their center of gravity in particular landscapes, where they absorbed their racial traits, until finally the storm of Islam, whose representation in map-form has not yet been attempted, swallows most of these nations—and thus religions. The group of these maps would teach us that it is once again the ancient trade and migration routes, already indicated by Stone Age findings, along which the spread of the great missionary religions then moved.

As a conclusion, a group of maps is necessary that summarizes Asia and Europe around 1000 AD as a unified area: This begins with the migration of peoples, which shakes the lands from the Chinese border to Spain and North Africa and scatters a new series of political forms over this vast distance, and concludes in the far west with the age of the Crusades, from which emerges the world of states of a new Culture3. And from there, along the immense ancient southern border of the Neolithic northern sphere, which now forms a border between forest and desert, through the Mongol invasions, which transforms the entirety of Asia, including Russia, into an area in which the ruins of ancient Cultures are overlaid by changing zones of power of various conquerors and tribes with their followers. From here on, the creative history of the world is essentially Western, that is, our own history.

[END OF TRANSLATION]

Thanks for reading! There are some more translations that will be coming out in the next few weeks. It’s shocking to me that it has taken nearly a hundred years for this gem to be translated. It should also be noted that I am no expert in cartography. It seems likely to me that at least some of Spengler’s suggestions have been incorporated in the last century. But it seems unlikely that they’ve been put to the morphological ends that Spengler had envisioned.

The next post will likely attempt to reconstruct some of Spengler’s sketches on prehistory (namely, the 10 articles he outlines in a letter to Hans Erich Stier). So please stay tuned for that.

And again, consider becoming a paid subscriber to support the project and to get access to exclusive content! — Spergler

The branch of zoology that deals with the geographical distribution of animals.–Tr

“Antike” was Spengler’s word for the Apollonian Culture of the Greco-Roman world. It corresponds to our use of “antiquity”. Though Spengler probably means it in a broader sense rather than just the Greek and the Romans.–Tr

The West-European Culture which Spengler dubs “Faustian Culture”.

Whenever I read a historical work I feel like I understand much better when I can use a map to track events. There is something to this

Taking Spengler’s Kartenbild literally, he has a great vision for an atlas. As you say, some of what he wanted has been created since then, but only in fragments that are mostly purpose-built for specific research topics. With the software we have today, Spengler’s maps could be built (ex: the thousands of structures being rediscovered in the Yucatán now). The geographic databases I have looked through are still largely inadequate for accomplishing this as they are, though. Would be a huge effort.