Spengler's Biography Part 1

From Birth to The Decline of the West (1880 - 1919).

A Quick Note

I am happy to announce the resumption of The Oswald Spengler Project. This post will serve as a biographical sketch of Oswald Spengler’s life from birth to the publication of the first volume of The Decline of the West in 1918. I plan on publishing these biographical interludes in between my posts explicating Spengler’s works. I hope this will grant the reader some deeper insight into Spengler’s mind and the background from which his work emerges. Please check the notes at the bottom of the post if you are interested in sources or reading more on Spengler’s biography.

The Early Days of Oswald Spengler

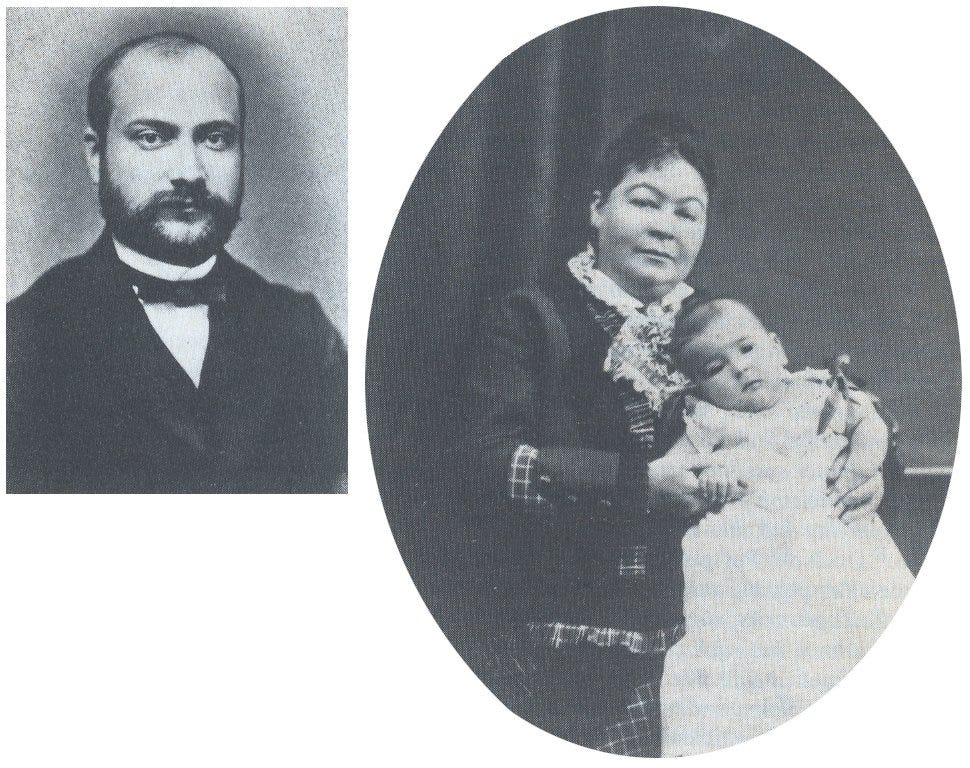

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler was born on May 29, 1880 in Blankenburg, Germany to Bernhard and Pauline Spengler. Blankenburg had historically been a mining town and was located on the north foot of the Harz Mountains. Spengler’s paternal grandfather had worked as a metallurgical inspector within the region. Blankenburg’s mining industry, however, began to decline and forced Oswald’s father, Bernhard Spengler, to abandon the family profession. Bernhard joined the German Empire’s civil service and worked as a postal official. This station afforded the Spengler family the comforts and advantages of a middle-class existence typical of Germany at the time. In 1886, Bernhard was promoted to a position in Soest and so the family moved.

While his father represented an austere and duty-minded influence upon the young Spengler, his mother’s side of the family represented a more artistic nature. Spengler’s maternal grandfather, Gustav Adolf Grantzow, was a ballet master married to a ballerina. Of their five children, two became actresses and one, Spengler’s aunt Adele, became an internationally acclaimed ballerina. Tragically, she would die before Oswald’s birth due to complications following the amputation of her right leg. Her fortune was left to her sister (Spengler’s mother), Pauline. Following the death of his mother in 1910, Spengler would inherit this money and used it to sustain himself as an independent scholar. Despite the Grantzows’ Bohemian proclivity toward the arts, Spengler’s mother was unloving and tyrannized the household. His duty-bound, humorless, and anti-intellectual father offered no comfort either. Later in life, Spengler remarked to his sister, Hildegard, that his hard and joyless childhood primed him for success later in life.

Growing up in such a household, the young Spengler was incredibly anxious as a child. Indeed, anxiety became a defining feature of the adult Spengler and his work. Spengler writes, “when I contemplate my life, it is one feeling which dominated everything, everything–anxiety”. In addition to anxiety, Spengler was frequently assailed by agonizing headaches. These migraines resulted in temporary losses of memory. In his autobiographical notes, a deeply unsettled Spengler confesses to suicidal thoughts. “I never had a month without thoughts of suicide”.

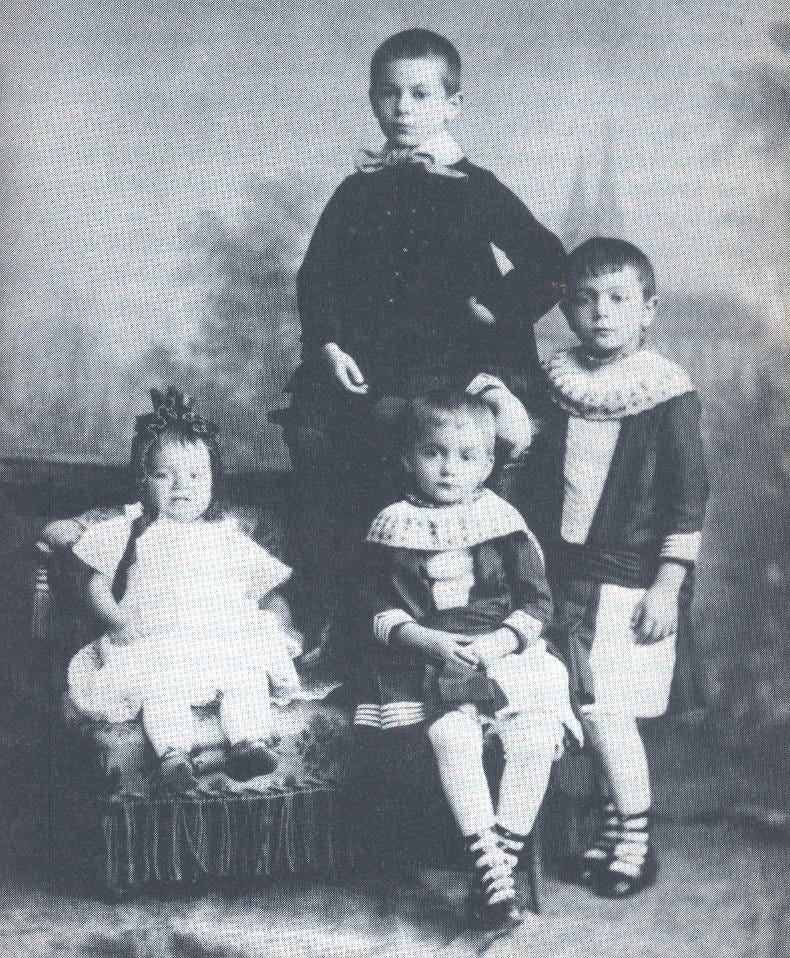

Despite the turbulence of his psyche, the young Spengler had an incredible imagination. Spengler would regale his three sisters with fabulous stories of an Arabian palace. He would fill booklets with drawings of maps and historical accounts of fictitious empires (one of which ended in revolution and military dictatorship—a theme continued in The Decline of the West). He would even include granular details like administrative procedures and economic statistics of his fictitious empires.

Though Oswald was clearly a bright and smart child, the Spengler family did not read much. His father reproached Oswald’s voracious appetite for reading. In his eyes, Oswald was meant to follow in his footsteps and become a dutiful government official. Intellectualism was to be despised. This tension between a life of duty and a life of the mind became central to Spengler’s later political and philosophical work. No doubt that Spengler’s intellectual proclivities were complicated by a desire to placate his father.

In the autumn of 1891, the Spengler family moved from Soest to Haale an der Salle. Spengler attended the local Latina (a secondary education institution that emphasizes the study of the classics and classical languages) where his favorite subjects were history and geography. Spengler would venerate his history teacher, Friedrich Neubauer, for the rest of his life. As part of the gymnasium’s curriculum, Spengler studied Greek and Latin for nine years. This study of the classics would become indispensable to the writing of The Decline of the West and its treatment of classical antiquity. Later, he would pick up some French and English (though only enough to read some specialized literature on archaeology and anthropology). He also learned Italian and eventually spoke it with reportedly acceptable fluency. While at university, he would become interested in his university’s Russian student population and taught himself to read his beloved Dostoyevsky with the aid of a dictionary.

As Spengler began to age into his late teens and early twenties, he began a number of literary pursuits. He was particularly interested in drama and drafted several historically-minded plays. These include a drama of the Roman emperor entitled, Tiberius; a series of Prussian dramas entitled Friedrich Wilhelm I, Friedrich II, Bismarck; an untitled cycle of North German tragedies; a dramatic composition of Jesus; a play on the Aztec emperor Moctezuma; a short story set during the Russo-Japanese war called Der Sieger (The Victor); and finally a libretto to Paul Strüver’s Dianas Hochzeit (Diana’s Wedding). Spengler only ever finished Moctezuma, Der Sieger, and the libretto. His other works were largely abandoned and Spengler’s sister, Hildegard, claims that Oswald burnt many of these early literary efforts in 1911.

At age 17, Spengler began to sneak into the University Library at Halle to supplement his omnivorous intellectual appetite. He began to steep himself in the works of Goethe, reading his entire oeuvre with the exception of those works pertaining to the natural sciences. Spengler knew the entirety of Goethe’s Faust part one by heart. He zealously studied the works of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer and worshiped Wagner’s music. He was so enchanted by a performance of Tristan in Bayreuth that he took up the piano just to play selections from Wagner. John Farrenkopf lists the following authors as also among the young Spengler’s favorites:

William Shakespeare

Gerhart Hauptmann

Henrik Ibsen

Maksim Gorky

Honoré de Balzac

Theodor Fontane

E. T. A. Hoffman

Heinrich von Kleist

Friedrich Hebbel

Heinrich Heine

Friedrich Hölderlin

Leo Tolstoy

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

August Strindberg

Émile Zola

Stendhal

Gustave Flaubert

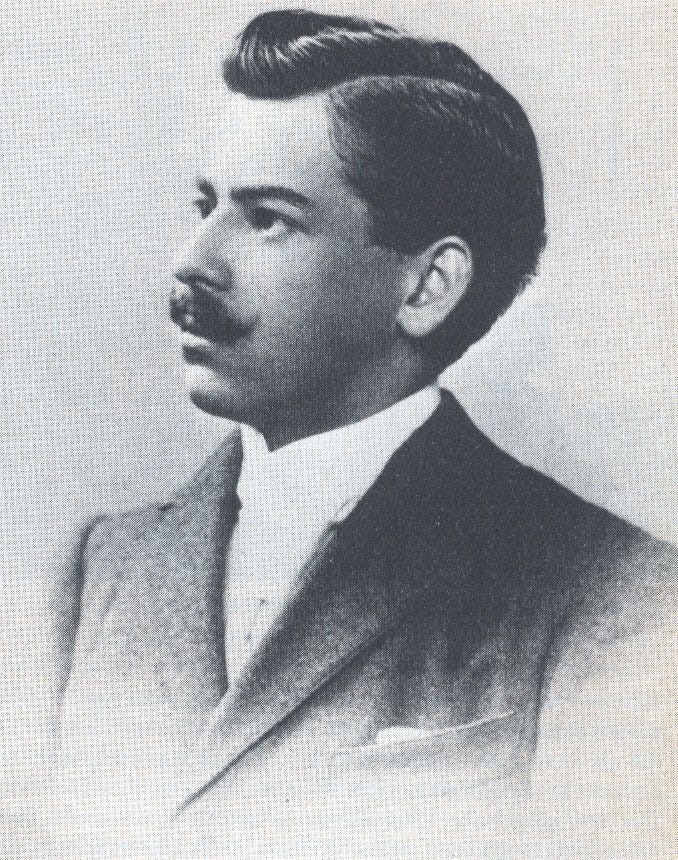

The Disappointing Career of an Ambitious Mind

In 1899, Spengler was awarded his gymnasial diploma. Biographer Anton Mirko Koktanek reports that this feat was capped by a Kanonenrausch–apparently a celebratory episode of excessive drinking common after graduation. His graduation signified entry into Imperial Germany’s educational elite. But the young adult Spengler was still forced to wrestle with choosing a career. On the one hand, his father expected him to be done with his studies and assume his civic duty through government service. On the other hand, Spengler’s deep intellectual passions were far from quenched. Spengler opted for the latter and enrolled at the University of Halle with the purpose of becoming a gymnasial teacher. His studies focused on mathematics and the natural sciences with a particular interest in Darwin and Ernst Haeckel. In all likelihood, it was around this time that Spengler became familiar with Goethe’s scientific works (though his biographers mention nothing of it). Though Ernst Haeckel is better known now as a German popularizer of Darwin’s works, Haeckel was more than familiar with Goethe’s works on anatomy, botany, and morphology. We must imagine that it was at this time when Spengler discovered “Goethean Science” (which would go on to have a profound influence on the construction of The Decline of the West and Spengler’s unique historical method).

In 1901, Spengler’s father passed away. The Spengler family moves out of Halle and back to Blankenburg (where Spengler’s mother, Pauline, had never wanted to leave in the first place). Rather than continuing his studies in nearby Halle, Spengler decided to transfer to the University of Munich. He wished to escape the joylessness of home life and loved Munich’s cultural vibrance and warmer climate. He also transferred to Berlin for one semester in 1902 (a relatively common practice in Imperial Germany) but found the city too soulless and megapolitan. Eventually, Spengler transferred back to the University of Halle and began to research his dissertation on the Greek pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus. Spengler, unfortunately, failed his first oral exam in the fall of 1903. Several errors precipitated this failure. For starters, he did not know any of his examiners. Spengler forewent seeking the approval of his advisor on his dissertation topic and failed to consult him altogether. Additionally, his examiners determined that Spengler had failed to adequately cite specialized literature on the topic. In April 1904, Spengler was afforded a second opportunity in which he passed his oral exam and was awarded his Ph.D. Again, I must speculate that Bernhard Spengler’s anti-intellectual influence was manifesting in Spengler’s rogue studies. Later in life, Spengler was offered many prestigious university jobs as department chairs–all of which he turned down. Despite Spengler’s intellect, the man had a serious distaste of academia and its–even then–drone army of “academicians”.

In the same year of being awarded his Ph.D., Spengler took the Staatsexamen, which was a series of exams required to enter the teaching profession. Spengler passed them in the fields of zoology, botany, physics, chemistry, mineralogy, and mathematics. In addition, he was required to write a specialized study to be admitted into the profession. He wrote a tract titled Die Entwicklung des Sehorgans bei den Hauptstufen des Tierreiches (The Development of the Organ of Sight by the Main Levels of the Animal Kingdom). Unfortunately, this work has been lost throughout the years. Spengler’s biographers refrain from further detail, but I have to wonder whether it has not survived (albeit, in a modified form) in Spengler’s Man and Technics. Part 2 (“Herbivores and Beasts of Prey”) discusses the importance of the evolution of binocular vision in predators and the impact of this physiological factor on the predator’s mind and behavior. However, since we do not have access to the original study and cannot compare the two, this connection is purely my own speculation.

Spengler was then offered a trainee position as a teacher in Lüneburg. Upon arrival, Spengler had a quick tour of the school and suffered a nervous breakdown on the spot. Biographer John Farrenkopf claims that the realization of being a “mere” teacher agonized the intellectually ambitious Spengler. But Spengler’s mother, Pauline, pressured Spengler into employment. He soon took up another position as a substitute teacher in Saarbrücken. Spengler took advantage of being on the border and traveled to France several times. He would look back on his time in Paris quite fondly for the rest of his life. It was also while in Paris he began to conceptualize the importance of city-life for culture and civilization. Versailles embodied a declining mature culture while Berlin was a megapolitan city of cultural philistines. Visits to French Gothic churches also planted in Spengler that the Gothic era (and not classical antiquity) served as the origin of Western Civilization. This idea would eventually grow into the cornerstone of Spengler’s argument in The Decline of the West.

Following this period on the Franco-German border, Spengler would spend a year teaching in Düsseldorf before shifting locations yet again. In June 1907, Spengler passed a technical exam for upper-level instruction in mathematics. Having some time between jobs, Spengler spent the summer traveling through Italy (perhaps mimicking Goethe who had done the same in his Italian Journey). Biographer John Farrenkopf mentions that, despite having a heart defect, this condition did not prevent Spengler from enjoying some hiking during his trip. His condition was, however, sufficient to have him declared medically unfit for military service in December 1907. Spengler was then offered employment at a Hamburg gymnasium at around the same time. So there he traveled. He received a promotion in the spring of 1908 and transferred to a different gymnasium within Hamburg. Spengler’s teaching offered an unusually broad assortment of courses including the natural sciences, mathematics, German, and history. By all accounts, Spengler was a good teacher. According to former students, his style was lively, and intuitive, with all the hallmarks of a good and passionate teacher. But the approval of his students did little to ease the disquiet in Spengler’s heart. The ambitious school teacher felt that his profession was beneath him. However, the job offered significant perks. A reasonably good income, ample free time for private study and travel, and the opportunity to teach the youth (which Spengler enjoyed throughout his life). He planned to stick it out for the time being.

Move to Munich as a Rogue Scholar

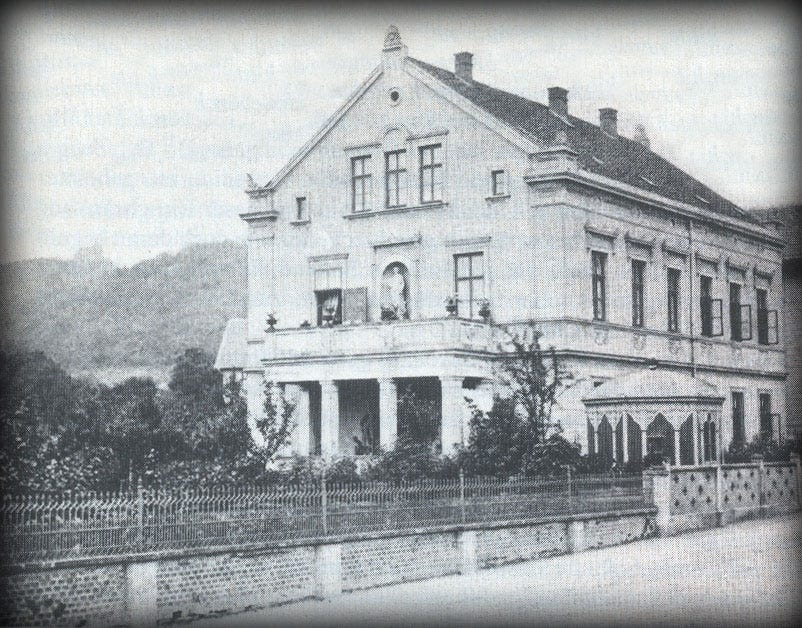

In 1910, Spengler set on making new opportunities for himself following the illness and death of his mother, Pauline. This marked a turning point in the otherwise unremarkable life of a Hamburg school teacher. Before she had even passed, Spengler requested a leave of absence and traveled straight to Italy. There, he felt the freedom of the southern air and the waning influence of an unloving and tyrannical matron. Free from her pressure, Spengler decided he would quit his job and seek a more daring life as a writer. In March 1911, he began an unpaid vacation in Munich and set out to become a writer in this south-German metropolis. The passing of his mother also meant Spengler’s inheriting of his aunt Adele’s wealth. Though it was sufficient for Spengler to quit his job, it forced Spengler to accept a markedly lower standard of living. Upon arriving in Munich, Spengler’s attention had not yet turned to a work on the philosophy of history. Instead, Spengler’s literary pretensions were inflamed by his bold personal moves. He aspired to write a major novel based on the sketches he created while at university. Many of Spengler’s surviving letters from this period detail his thoughts on the Munich art scene along with his own literary efforts. According to his sister, Spengler was also engaged as an art critic by two Munich newspapers. Munich served as a symbolic ground for the now-free Spengler to metamorphose his life into something far greater. He deeply loved the city, its temperate weather, and being at the gateway to southern Europe. Munich was to be Spengler’s home for the rest of his life.

But this honeymoon period with an artist’s life soon turned sour. He concluded that poetry and drama had terminated as meaningful modes of artistic expression. They had simply run their course. The only medium yet to be exhausted was the novel. And that someone from his generation would be the one that would “exhaust the sum total of the life of [his] epoch,” as Goethe had done in Wilhelm Meister and Stendhal in The Red and the Black. He found Thomas Mann to be an unwitting romantic and therefore inappropriate to emulate in a post-romantic era. Spengler yearned to see a “new German master prose” with a “Hindenburg style” that would command center stage in German letters. It’d be “concise, lucid, Roman, above all natural”.

The decline of the arts was not Spengler’s only concern. German politics weighed heavily on Spengler’s mind ever since the resignation of Otto von Bismarck in 1890. Germany was seemingly on the decline and crises were mounting in Europe and across the world. Spengler estimated that Germany lacked a cunning-enough leader to guide the nation through the coming turbulence of world politics. This would spell Germany’s doom. Further, the Agadir Crisis of 1911 brought the possibility of a general European war to the forefront of everyone’s minds. In the introduction to The Decline of the West, Spengler comments on the impact of the Agadir Crisis on his decision to write the book.

His literary pretensions evaporated and Spengler became determined to write a slim volume dealing with the contemporary position of Germany in world politics under the provisional title of Liberal and Conservative. The book would have focused on the coming war between England and Germany and the differing political ethos between the two (England being liberal and Germany being conservative). However, the scope of the book grew and mutated over time. In 1912, he passed a Munich bookshop and saw a window display of Otto Seeck’s work Geschichte des Untergangs der antiken Welt (The History of the Decline of the Ancient World). He thereupon conceived the title of his own budding work as a conscious parallel. Equipped with a new title–Der Untergang des Abendlandes–Spengler decided to place Liberal and Conservative on the back burner. By the time Spengler returned to it, it transformed into Prussianism and Socialism and was published in 1919 (after releasing the first volume of The Decline of the West).

As Spengler began to write the book, the first World War began. He buried himself in his work and became increasingly isolated. Correspondences with old friends became increasingly sporadic and the privations of the wartime economy began to exert hardship on the independent writer. Spengler, who was something of an epicurean in his tastes, relished excellent food, wine, and cigars. The English blockade of Germany imposed nationwide shortages of food and fuel. Consequently, what little Spengler did eat was bland and contributed to his malnutrition. A shortage of gas forced him to write by way of candlelight at night. And the lack of heating fuel forced Spengler to place a chair on top of his desk. Spengler would precariously climb up his desk and sit on the elevated chair so as to be closer to the warmer air that was near the ceiling. But despite these austere measures, Spengler anticipated his work to become a tremendous success. He wrote, “[it] will, to be sure, arrive upon the scene of contemporary literature like an avalanche in a shallow pond”.

But these personal privations paled in comparison to the tragedies which afflicted the Spengler family during the war. His sister, Adele, committed suicide in 1917 at the age of thirty-five. The following year, Spengler’s brother-in-law, Fritz Kornhardt, fell on the field of battle. Despite the tragedies and hardships of the wartime years, Spengler pushed on and eventually had a manuscript in early 1917. Spengler began the search for a willing publisher but a paper shortage delayed the work’s publication. Eventually, Braumüller in Vienna accepted it and published it in April 1918.

Shockingly, the book was immediately successful and even something of a bestseller. In the translator’s preface to The Decline of the West, Charles Francis Atkinson remarks the following: “the public impulse to read it arose in and from post-war conditions, and thus it happened that this severe and difficult philosophy of history found a market that has justified the printing of 90,000 copies. Its very title was so apposite to the moment as to predispose the higher intellectuals to regard it as a work of the moment–the more so as the author was a simple Oberlehrer and unknown to the world of authoritative learning”.

The quick success of the book helped the rather dire financial situation of its author. The Nietzsche Foundation awarded Spengler the Lassen Prize in November 1919. Spengler catapulted into the many aristocratic, scholarly, and political circles of contemporary German society. Despite his entry into this intellectual elite, Spengler’s work drew the ire of many “experts” in theology, history, science, and art criticism. In 1922, Manfred Schroeter published Der Streit um Spengler–an attempt to catalog and refute Spengler’s many critics. Many of these criticisms tended to nitpick details in an effort to “disprove” Spengler’s radical theory of historical determinism. They largely failed to see the forest for the trees and could not grasp the true depth of Spengler’s argument and methodology. Schroeter’s index of critics’ names reaches an astonishing 400 entries. Suffice it to say that, though it was popular, Spengler’s work was highly controversial. The criticisms of the first edition spurred Spengler to rework the volume and release a revised edition in 1922. This revised edition has become the standard edition and the one upon which the English translation is based.

This concludes Spengler’s biography up to the point of the work’s publication and popularization. From here, I will be pausing Spengler’s biography and transitioning into a chapter-by-chapter review and exegesis of The Decline of the West. The biographical interludes will continue as bridges between Spengler’s major works. Expect the next post to arrive sometime later in February. I will be discussing the introduction to The Decline of the West and the philosophical influences of Nietzsche and Goethe upon Spengler.

If you are interested in reading more about Spengler’s life and works, I would recommend John Farrenkopf’s book The Prophet of Decline (published by LSU Press in 2001). It is by far the best English source on Spengler’s life and works. Farrenkopf wrote the book after extensive research on Spengler’s estate at the Bavarian State Library. H. Stuart Hughes also has a book on Spengler’s life and works but it gets a few things wrong so I am hesitant to recommend it. If you can read German, Anton Mirko’s book Oswald Spengler in seiner Zeit is highly recommended and is considered the “definitive” biography of the man. Additionally, Spengler’s autobiographical notes, Eis heauton, are worth reading.

A special thanks to @AMonophtalmos for sending me the photos of Spengler.

Ducunt Fata volentem, nolentem trahunt.

This is amazing

This is wonderful!