Morphology and History

Schopenhauer and Spengler on the Possibility of a Science of History

Schopenhauer against History

The first step into any scientific inquiry is to define parameters and guiding principles. What am I studying? What sort of thing is it? How do I study this thing? To the natural sciences, this is a fairly intuitive process. A zoologist focuses on animals; a botanist studies plants; a physicist delves into the laws governing matter. Prior to dissecting a specimen, a zoologist, for instance, can anticipate certain characteristics based on its classification. Take a whale, for example. Knowing it belongs to the class Mammalia, the zoologist can expect to find lungs, seven cervical vertebrae, a diaphragm, and other traits. Similarly, a botanist anticipates features like leaves, flowers, fruit, and roots in a tree specimen. Both scientists rely on generic concepts that govern their respective specimens.

Since its inception, philosophy has harbored aspirations of universality. Anything discernible through systematic inquiry is deemed within the realm of philosophy. Aristotle's extensive works, spanning from metaphysics to biology, politics, poetics, logic, and beyond, exemplify this expansive domain. However, a particular discipline has emerged, sparking considerable debate among philosophers—History. While philosophy speaks of the universal and the eternally true, History appears to be the ephemeral study of things past. By its nature, History never refers to the eternally true but only to the multitude of passing events, epochs, and great men. Can History belong to philosophy?

The central problem with History is its lack of a universal. Unlike the natural sciences, which categorize physical specimens under generic concepts (i.e., genera), History presents an ever-expanding collection of specific instances seemingly disconnected from any overarching universal. In a short essay titled On History, Schopenhauer expounds on this issue. He argues that History cannot be treated as a science akin to the natural sciences. In scientific inquiry, repeated examinations of physical specimens enable the formulation of general laws to which particulars must adhere. For instance, a scientist dissecting a whale, a dolphin, a manatee, and a shark can observe common features such as vertebrae, lungs, and mammary glands in the first three specimens. These shared characteristics allow for their grouping under a generic concept, perhaps "aquatic mammals." The shark, however, insofar as it is lacking some of these traits, necessitates a distinct classification.

Schopenhauer states that this subjective nature of History prevents us from studying it systematically. Consequently, it is of less value than something like poetry in ascertaining the essence of man.

History alone cannot properly enter into this series, since it cannot boast of the same advantage as the others, for it lacks the fundamental characteristic of science, the subordination of what is known; instead of this it boasts of the mere coordination of what is known… History would accordingly be a science of individual things, which implies a contradiction.

To make matters worse, our object of inquiry is far more nebulous than those of the natural scientist. We have no problem picking out a whale in the ocean or the tree swaying in the wind. Their immediate appearance to our sense-perception “specimens” content us to the fact of their reality. In fact, the issue would likely never even occur to the scientist. Biological entities exhibit clear borders. Where the whale begins and ends is immediately apparent to our senses. Historical phenomena lack such immediate perceptibility. We rely on mental reconstructions gleaned from biographies, documents, speeches, and other sources to comprehend historical events. “No man can judge history but one who has himself experienced history”, says Goethe. Whatever mediates subject and object is cursed by a historical distance. It's akin to a zoologist having to study a beast solely based on historical descriptions rather than dissecting a tangible specimen on a lab bench.

The historian has no luxury of species, stable types, or dissection and experimentation. His “specimens” are events, leaders, governments, and so on. Pericles, the rule of the Thirty Tyrants, the Peloponnesian War, etc. These are things which existed only for a short slice of time. Consequently, the notion of a "science of individual things" within history becomes problematic because there is no universal "type" to which these specimens must adhere. Each historical occurrence is unique, defying classification under overarching categories or types. Schopenhauer illustrates his point by writing,

Thus I may know in general about the Thirty Years’ War, namely that it was a religious war waged in the seventeenth century; but this general knowledge does not enable me to state anything more detailed about its course.

To Schopenhauer, knowing the “type” of war which occurred tells you nothing about the war that actually occurred. Wars within the same "type" exhibit such diverse and numerous variations that claiming to possess generic knowledge for judging them appears absurd. Generic knowledge thrives in disciplines characterized by uniformity and regularity, which is not the case in history. The zoologist does not worry about this since every generation of bats, whales, and dogs are roughly the same. Between specimens of the same species, variation is minimal and easily accounted for. Unlike the relative consistency found in species studied by zoologists, history is replete with such idiosyncrasies that to speak of generic knowledge yields the historian a superficial understanding at best. Therefore, History seems to be in crisis. Many of Schopenhauer’s contemporaries (Hegel and his successors especially) were so eager to treat History as a science, that they ignored this issue. History, the realm of the artificial events of man’s own doing, has no universal. There can be no catalogues of types nor can there be any investigations into the “essence” of historical phenomena. It seems impossible.

But let’s not dismiss the possibility of a Philosophy (or Science) of History on Schopenhauer’s sagacious counsel alone. Let’s consider our parameters once more.

What is it? What sort of thing is it?

“History” is a broad classification. Taken literally, it would simply mean everything that has ever happened. Perhaps this classification is too broad. If we are seeking generic knowledge subsumed under universal types, we should articulate these types. No wonder that History, itself a type of universal, cannot be subsumed into meaningful genera without stripping the importance of particulars. Schopenhauer's observation highlights an issue with taxonomy rather than a definitive pronouncement on the limitations of historical inquiry. It follows that we might reconsider our Science of History by focusing on specific types of phenomena rather than attempting to encompass the entirety of past existence.

In his Politics, Aristotle characterizes humans as "political animals," highlighting their inherent inclination towards communal living and the formation of cities, which serve the purpose of fostering a good life. Shortly after, Aristotle contrasts this with the communal life of bees. The main difference between bees and humans is less important for the question at hand. It boils down to human rationality and speech versus the bees who act by instinct alone. What’s important here is the use of the bee colony as a natural social entity. Understanding the behavior of bees necessitates reference to the colony as a whole. We speak of the particular roles of male drones, female workers, forager bees, and the queen bee insofar as they contribute to the activity of the colony. These individuals form a greater whole that lends itself nicely to our inquiry. Drawing parallels to humanity, we can similarly examine the collective wholes that humans form and participate in. In other words, we can study the bee colony as a natural whole through a natural-scientific lens. Why can’t we do the same for human communities?

So are we still “historians”? Perhaps not if we still use Schopenhauer’s understanding of History as the totality of all past events. But if we focus on a single “type” of phenomenon (one that permits generic knowledge), we might still be historians of something. But of what?

To list off a few of these natural wholes: cities, states, nations, and cultures. Thus, our object of inquiry becomes slightly less nebulous. Just as Aristotle described humans as “political animals”, we might take Spengler’s works and say we humans are “cultural animals”. What is Culture? As Nietzsche says, “unity of style”. But what is style? As Spengler perhaps ineloquently explains in his chapter, The Meaning of Numbers, it relates to unique cultural perceptions of time and space. These perceptions are manifest in a Culture’s architecture, art, mathematics, politics, and more. The Western sense (or style) of infinite space can be felt in their Gothic cathedrals, their contrapuntal music, their calculus, and so on. Likewise, Greco-Roman antiquity’s sense of the corporeal and the here-and-now can be felt in Dorian temples, their sculptures, their geometry, and so on. Insofar as we feel these different prime-symbols (again, styles), we can identify different Cultures. Exactly how we “physiognomize” the soul of a Culture to pick up on these prime-symbols will have to be the subject of another article. For now, let us accept that we have these Cultures as objects of inquiry, that they can be manifestly identified, and that, just like the bee colony, they are subject to generic knowledge.

Spengler and Cultural History

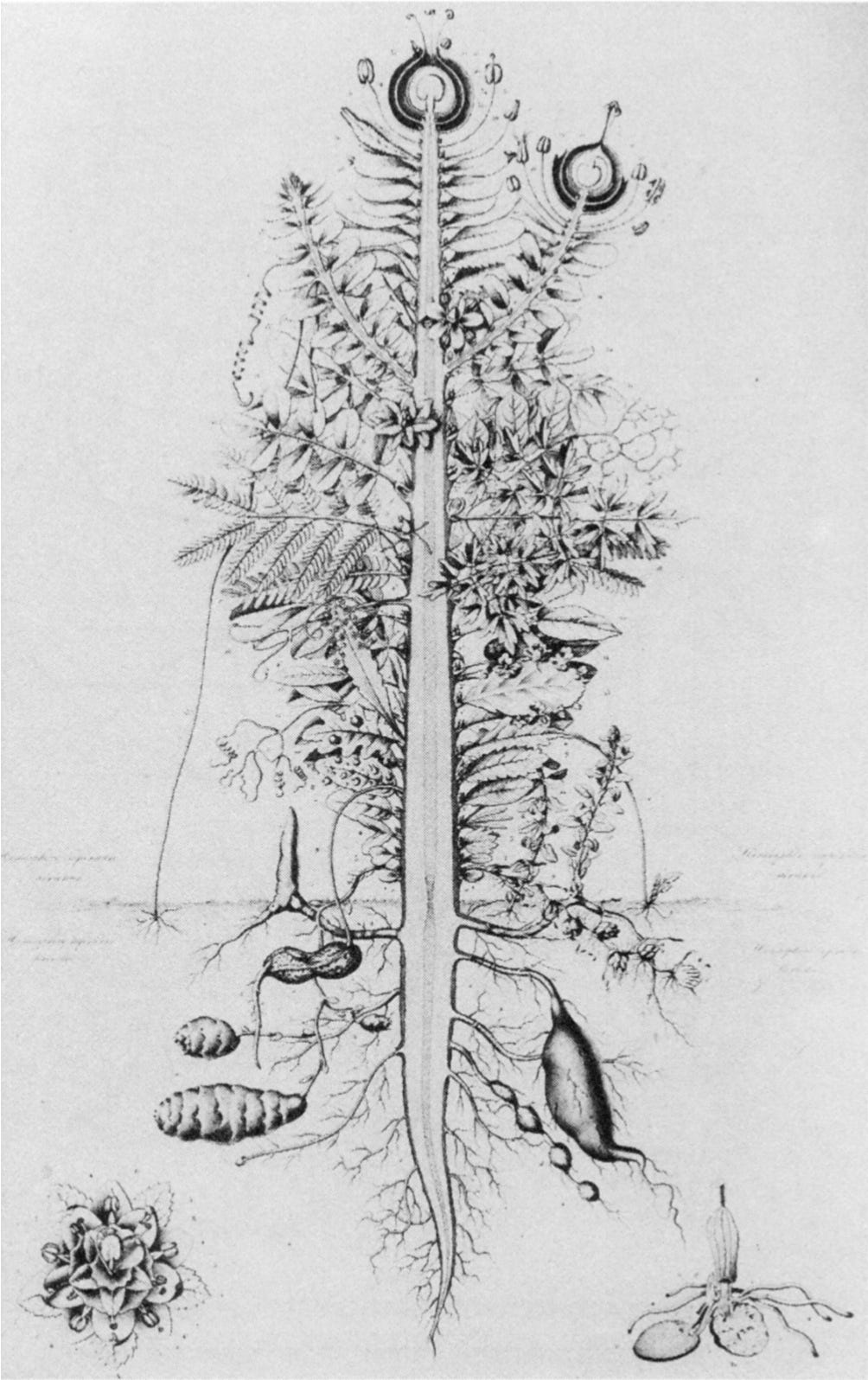

Spengler, in the preface to the revised edition of The Decline of the West, mentions two influences: Goethe and Nietzsche. Goethe, he says, gave him method. Goethe wrote a number of unorthodox treatises on science—primarily on botany, zoology, and color theory. The first two are concerned with the issue of morphology—that is, the study of forms. Goethe’s goal in these researches was to uncover the archetypes which underlie all organisms and explain the development of their bodily shape. In his Metamorphosis of Plants, Goethe describes the developmental stages plants undergo as they move from seed to plant to flower to fruit and thus finish their development. Through repeated observation and the use of a peculiar faculty of mind—what Goethe calls “exakte sinnliche Fantasie” [exact sensorial imagination]—the scientist allows the underlying form of the organism to impress itself upon his mind and reveal itself. He is meant to “grow” a plant in his imagination and intuit its developmental principles and ascertain a deeper reason for their “becoming”. Doing so revealed the Urpflanze or the Archetypal Plant to Goethe. Returning to Schopenhauer’s description of the natural sciences, these morphological archetypes constitute generic knowledge to which all manifestations of a species accord. A universal with which to understand the particulars.

Spengler, armed with Goethe’s method, seeks to do something similar in the study of Culture. The book itself is subtitled “An Outline of a Morphology of World-History”. His goal is to demonstrate that, just as Goethe successfully found the archetypal Urpflanze in botany and the vertebrate “typus” in animals, Spengler could uncover the archetype governed the growth and decay of Cultures. Doing so might offer the sort of generic knowledge in a historical discipline which Schopenhauer found impossible.

While laudable in his efforts, such an approach hinges upon a few questions. First, we must understand that Goethe’s Naturphilosophie was meant for the natural world. It is a science of organisms. Whether human Cultures constitute organisms (or perhaps superorganisms) is not a clear cut matter. It requires us to affirm the proposition that “humans are cultural animals” and together they can create a natural whole which avails itself to this science of organism. To his credit, Spengler doesn’t shy away from this issue by stating “Cultures are organisms, and world-history is their collective biography” (DOTW, 104). Spengler, however, presents this more as an article of faith rather than a carefully argued proposition. But to strengthen his point, he refers back to Goethe:

In the works of the old-German architecture one sees the blossoming of an extraordinary state. Anyone immediately confronted with such a blossoming can do no more than wonder; but one who can see into the secret inner life of the plant and its rain of forces, who can observe how the bud expands, little by little, sees the thing with quite other eyes and knows what he is seeing.

Elsewhere, Spengler cites Goethes’ essay Geistesepochen as further justification that Goethean Science might fruitfully be applied to the study of Culture. For a breakdown of that essay, read my last piece.

Goethe on the Four Stages of Culture

Goethe's essay, Geistesepochen [the stages of Man's Mind] and its influence upon Spengler's Decline of the West.

Now that we have established that Culture is an appropriate object of inquiry, there still remains a question about the methodological “hook-up” between mind and world. How do we best study this thing? How do we mediate subject and object? In other words, what is our version of a “dissection on the lab bench”?

Spengler creates an opposition between two world-pictures. The World-as-Nature and the World-as-History. He opts for the latter as a better means of piercing the phenomenal veil and uncovering the essence of Culture. He writes:

All modes of comprehending the world may, in the last analysis, be described as Morphology. The Morphology of the mechanical and the extended, a science which discovers and orders nature-laws and causal relations, is called Systematic. The Morphology of the organic, of history and life and all that bears the sign of direction and destiny, is called Physiognomic.

Spengler is telling us that his physiognomic approach to morphology will look rather different from what is commonly practiced in the natural sciences. He has little interest in causality, laws, and systems. His approach is concerned with life, symbolism, and the ever-mysterious becoming peculiar to the organic world. But how to intuit these essences? Spengler clues us in by writing:

I distinguish the idea of a Culture, which is the sum total of its inner possibilities, from its sensible phenomenon or appearance upon the canvas of history as a fulfilled actuality. It is the relation of the soul to the living body, to its expression in the light-world perceptible to our eyes. This history of a Culture is the progressive actualizing of its possible, and the fulfillment is equivalent to the end.

The works of a Culture—its art, mathematics, etc.—exist as actualities which emerge from a latent potentiality. From the actualities, which are outward appearances, he is able to intuit the idea of a Culture. These are confessions of the soul. Elsewhere, Spengler writes:

In every science, and in the aims no less than in the content of it, man tells the story of himself. Scientific experience is spiritual self-knowledge. It is from this standpoint, as a chapter of the Physiognomic, that we have just treated mathematics. We were not concerned with what this or that mathematician intended, nor with the savant as such or his results as a contribution to an aggregate of knowledge, but with the mathematician as a human being, with his work as a part of the phenomenon of himself, with his knowledge and purposes as a part of his expression. This alone is of importance to us here. He is the mouthpiece of a Culture which tells us about itself through him, and he belongs, as personality, as soul, as discoverer, thinker and creator, to the physiognomy of that Culture.

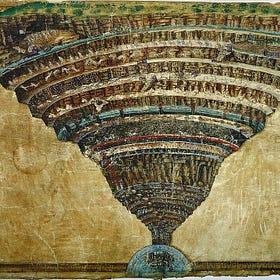

This is what it means to uncover the morphology of Culture. It is to physiognomize these mouthpieces of Culture and uncover the idea working itself through them. From there, we trace the development of these ideas. The moment they are born, how they appear in Cultural productions, how they rhythmically work toward perfection and once apotheosized begin a process of decline until the idea itself is dead. This presents a morphology of the Cultural “typus”. Every living organism is bound by birth and death. It has a predictable lifespan and moves through immediately recognizable developmental stages. Spengler likens it to the seasons, with each Culture having a spring, summer, autumn, and finally a winter signifying death.

The history of Cultures viewed morphologically allows for some fascinating insights. Spengler employs the terms “homology” and “contemporary” to signal the equivalent importance of historical facts across Cultures. Homologous figures appear contemporaneously in regard to their position with their respective Cultures. Suddenly, Descartes and Pythagoras appear side by side. The Trojan War and the Crusades become contemporary. Polycleitus pairs in time with Bach. Now armed with generic knowledge—created as a result of an in-depth study of the world’s eight high and mighty Kulturen—we can better understand the particular facts of this or that Culture. They are all positioned as part of a greater historical becoming.

Lastly, this offers us some insight into the most enticing aspect of Spengler’s study of Culture. From the outset, Spengler makes clear the importance of such a work:

In this book is attempted for the first time the venture of predetermined history, of following the still untraveled stages in the destiny of a Culture, and specifically of the only Culture of our time and on our planet which is actually in the phase of fulfillment—the West-European-American.

Later on in Chapter 3 we see a similar sentiment:

Overpassing the present as a research-limit, and predetermining the spiritual form, duration, rhythm, meaning and product of the still unaccomplished stages of our western history; and reconstruction long-vanished and unknown epochs, even whole Cultures of the past, by means of morphological connexions, in much the same was as modern palæontology deduces far-reaching and trustworthy conclusions as to skeletal structure and species from a single unearthed skull-fragment.

Spengler is convinced he has uncovered the logic of History—at least as it applies to the reign of High Cultures which has been the last 6000 years or so with the end of the Neolithic. These morphological connections are built on a sort of generic knowledge of how Culture must be. These are the inward principles which regulate the development of Cultures. Knowing this tells us how our western history must necessarily develop moving into the future. Just as every preceding Culture underwent periods of Caesarism, Cultural decay, chaos, and finally death, so must ours.

This was Spengler’s dream. To revolutionize the study of History and to arm the historian with new methodological tools to help recreate the many great forms whose day has long since passed. Spengler writes:

This is a truly Goethean method—rooted in fact in Goethe’s conception of the Urphänomen—which is already to a limited extent current in comparative zoology, but can be extended, to a degree hitherto undreamed of, over the whole field of history.

Whether Spengler was successful in realizing this dream is a bit more difficult to state. Others took up the mantle of broad and sweeping views of history and civilizations. Toynbee comes to mind as does Braudel. But none had that physiognomic tact which makes Spengler feel so special. One gets the impression that he really did pierce the veil, peek his bald head into the clouds, and bear witness to History’s shimmering forms and archetypes. He speaks not only to the vital pulse that exists within a Culture but also the vital pulse inherent in his readers (young men of the Faustian West). It serves as a poem that synchronizes our own sense of fate with that of an entire Culture. We are wrapped up in this greater Destiny. We can participate willingly and heroically or find ourselves dragged by the Fates. And of course, Spengler hoped his work would encourage these young men “to devote themselves to technics instead of lyrics, the sea instead of the paint-brush, and politics instead of epistemology”. This plea has seemingly fallen on deaf ears. Maybe that was inevitable. When you write a colossal two volume tome on the history of Culture, you naturally attract a bookish type of reader. But what of those of us who feel more attracted to epistemology instead of politics? Spengler has given us this new method, inherited by way of Goethe, to excavate a great wealth of lost Cultures, nations, and historical phenomena. And like that paleontologist, we might be guided by a sense of inward necessity and organic logic to help reconstruct what’s been lost to history. As Spengler says, “does history only exist when it is written in books?”

Very interesting survey of this topic. I know it may be too early to know, but do you have any soft targets for the completion of your book? Just curious.