An Introduction to Spengler’s Decline

From Chapter 2 of John Fennelly’s Twilight of the Evening Lands

The following is from John Fennelly’s book, Twilight of the Evening Lands. It is a rather succinct and sympathetic introduction, so I figured it would be worth sending to you all. I’ve gone ahead and added some images that I think help further elucidate Spengler’s main ideas. Enjoy!

FENNELLY

The Spenglerian Theory of cultural growth and decay is not difficult to understand provided two conditions are met. First, it is necessary to grasp the unusual meanings which the author attaches to certain key words. Second, one must brush aside the smoke screen of metaphysics with which he surrounds and beclouds his approach to the subject.

Spengler describes his work as a Morphology of History. By this he means the treatment of each separate culture as a living organism which is born, grows, decays and dies within the framework of a fixed and predictable life-cycle, just like any other living organism. He employs the word Culture to describe the living and creative phase of this organism, and Civilization as the end term of every culture, a period when all genuine creativity has disappeared, and the culture approaches its final demise under the bright glare of cold, abstract reason.

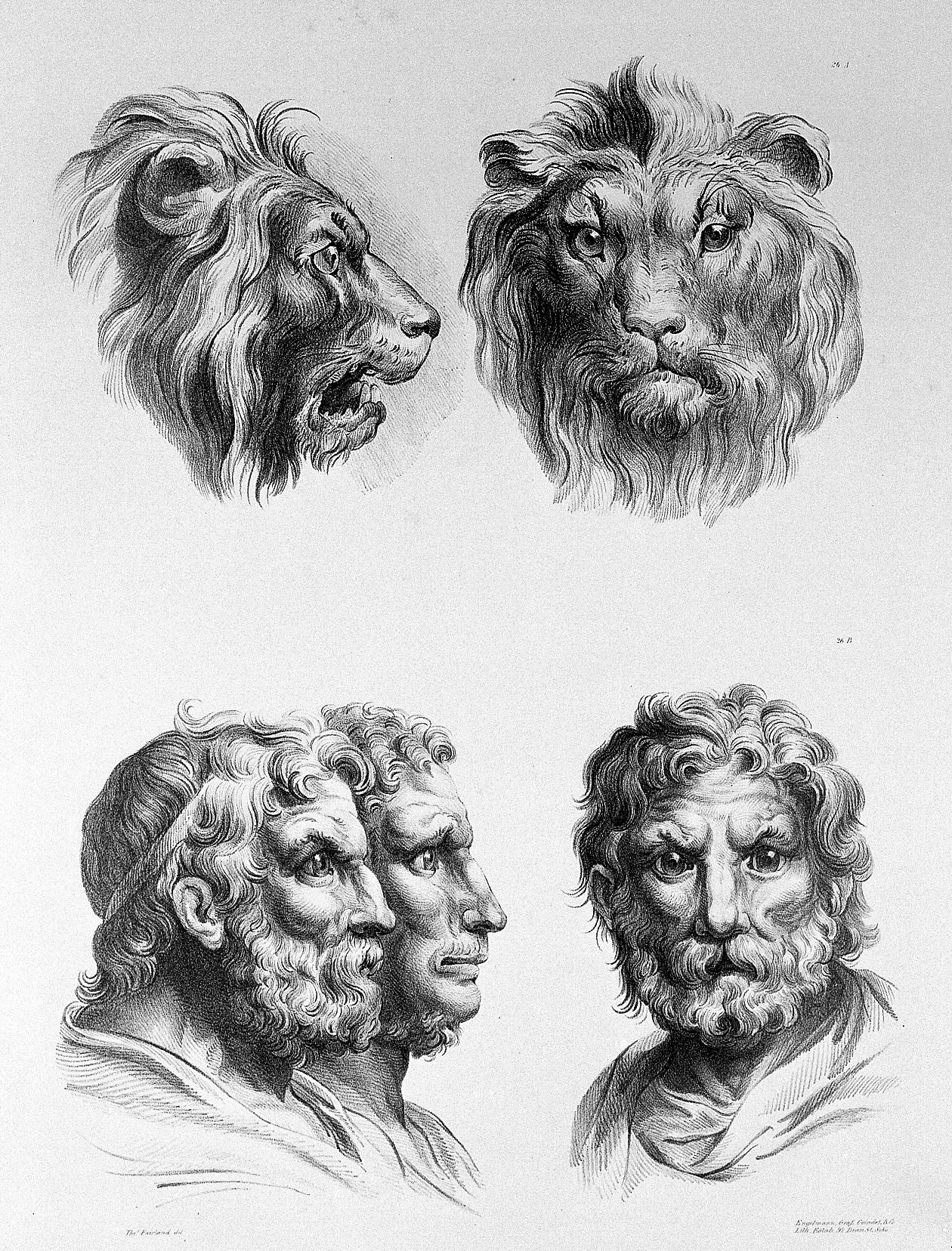

The next key-word encountered is physiognomic, the literal meaning of which is "pertaining to the face." Spengler uses it, however, to describe his intuitive approach to the problems of history;—looking directly into the face or the heart of historical events, rather than attempting to understand them by means of scientific analysis. Spengler also makes a rigorous distinction between two kinds of time. The first is the time of history, time as duration, which is irreversible, and which gnaws inexorably into the future. The second is the time of mathematical law, represented by the symbol t, which is reversible, and which is an abstraction from reality. The first relates to destiny and the second to the principle of causality.

These two concepts could lead us directly into the heart of Spengler's metaphysics, but discussion of this subject must be postponed until later in the study. At this point it will suffice to state that Spengler was convinced that the real essence of history could only be grasped by means of the physiognomic or intuitive approach.

In order to clear the ground for his theory of comparative cultures Spengler first launches a vigorous attack on the conventional classification of "Ancient," "Medieval" and "Modern" histories. He describes this classification as "an incredibly jejeune and meaningless scheme," an egocentric conception of our western Culture which treats all past history merely as a backdrop to present day life in Europe. This conventional treatment of history is designated as the Ptolemaic system, in which all the other cultures are made to follow orbits around western Europe as the presumed center of all world events. Spengler describes his own method as the Copernican system which admits no priority in the treatment of anyone culture in relation to all of the others.

Thus, in place of a linear concept of history leading up to and culminating in a picture of our own times, Spengler presents the story of eight separate High Cultures of the human race, no one of which is considered more important than any of the others. These eight are: the Babylonian, the Indian, the Chinese, the Egyptian, the Classical (the Culture of Greece and Rome), the Arabian (also called the Magian by Spengler), the West European (or Faustian) Culture, and finally the Mayan-Aztec Culture of Mexico.

Each of these cultures is treated as a separate living entity with a definite limited life-cycle of approximately one thousand years, during which it actualizes all of the possibilities inherent in its own particular Weltanschauung (world-outlook). The civilization phase of a culture, however, may last for hundreds or even thousands of years more, while life continues in a kind of petrified state.

With this background one can grasp Spengler's idea of the birth and development of a culture, and of the contrast between culture men and mankind as a whole. In one magnificent paragraph he sums up this philosophy:

"Mankind, however, has no aim, no idea, no plan, any more than the family of butterflies or orchids. 'Mankind' is a zoological expression, or an empty word . . . I see, in place of that empty figment of one linear history which can only be kept up by shutting one's eyes to the overwhelming multitude of the facts, the drama of a number of mighty cultures, each springing with primitive strength from the soil of a mother-region to which it remains firmly bound throughout its whole life-cycle, each stamping its material, its mankind, in its own image; each having its own idea, its own passions, its own life, will and feeling, its own death. . . . Each culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression which arise, ripen, decay, and never return. There is not one sculpture, one painting, one mathematics, one physics, but many, each in its deepest essence different from the others, each limited in duration and self-contained just as each species of plant has its peculiar blossom or fruit, its special type of growth and decline. . . . I see world-history as a picture of endless formations and transformations, of the marvelous waxing and waning of organic forms. The professional historian, on the contrary, sees it as a sort of tapeworm industriously adding on to itself one epoch after another."

One may search the pages of the Decline in vain for a precise explanation of the birth of a culture; why it appeared, when and where it did, and why it emerged with its own particular world-outlook. It seems clear that Spengler regarded these phenomena as part of the eternal mysteries of life: "A Culture is born in the moment when a great soul awakens out of the proto-spirituality of ever-childish humanity, and detaches itself, a form from the formless, a bounded and mortal thing, from the boundless and enduring."

The author does throw some light, however, on the type of world-outlook that emerges in a particular culture by intimating that the surrounding landscape is a determining influence in shaping the soul of a culture. Thus, he sees in the hard, bright light of the Mediterranean a basic cause in shaping the Classical Culture, and the dark forests of northern Europe as a prime influence in shaping the brooding soul of Faustian man.

In the simplified and condensed explanation of Spengler's culture theories presented below, attention is concentrated very largely on only three of the eight cultures; the Classical, the Arabian or Magian, and the West European or Faustian, with occasional side glances at the others. Actually this was the course followed by Spengler himself. No one man could possibly have the breadth of knowledge sufficient to cover with equal facility and understanding all parts of the enormous area staked out in the Decline. The author was an accomplished Classical and West European scholar, with an adequate but more limited knowledge of the Magian and Egyptian Cultures. His understanding of the Babylonian, Indian and Chinese Cultures, however, was more superficial, and was practically non-existent in the case of the Mayan-Aztec Culture. As a result, a more understandable account can be presented by sticking closely to the areas in which Spengler was most proficient. Moreover, the exposition in this chapter attempts only to cover the broad phases and turning points of the growth and decline of the several cultures

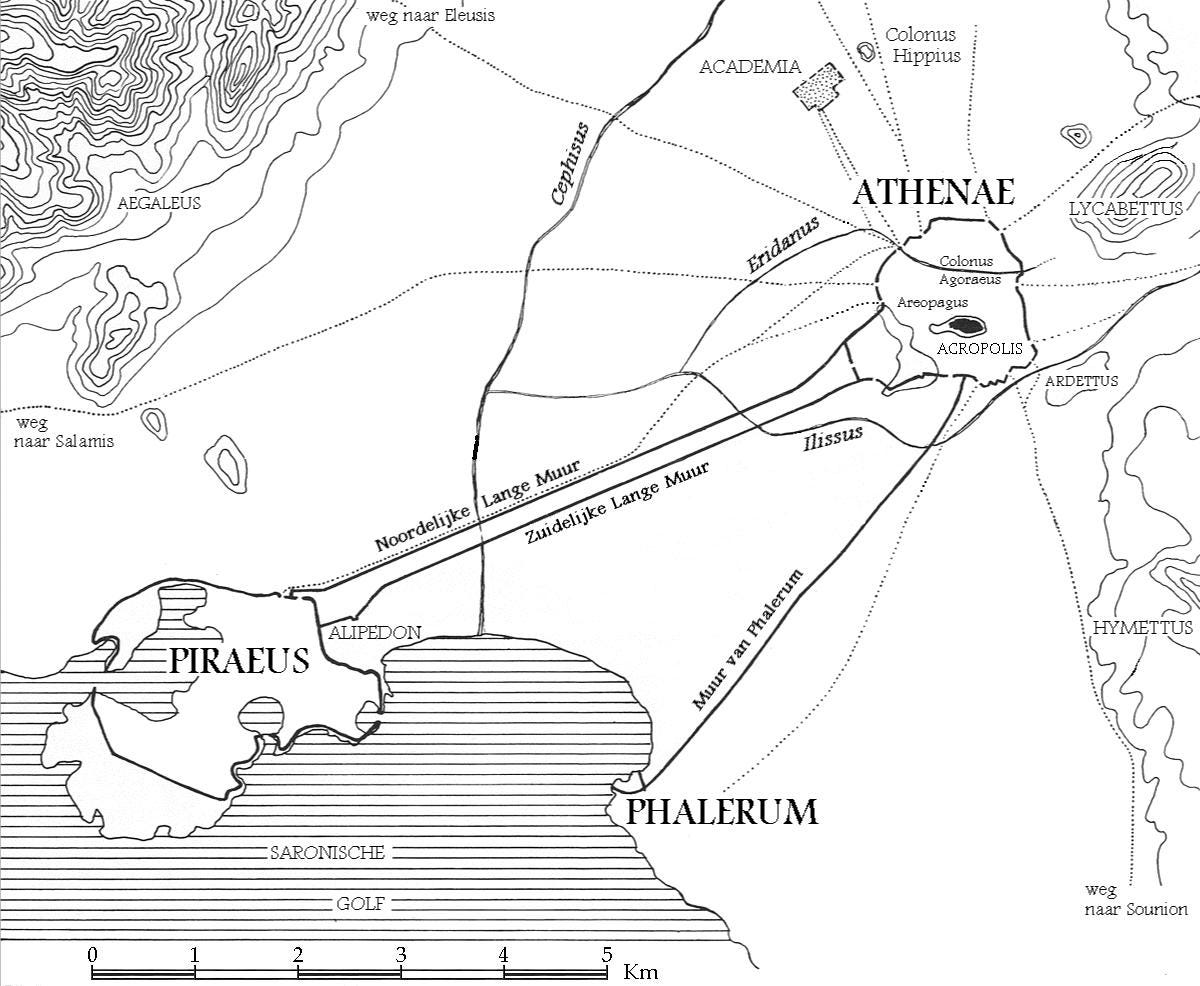

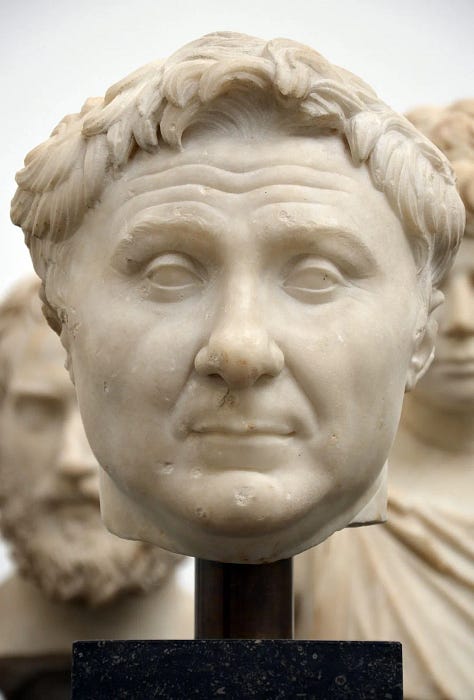

The prime symbol of the Classical Culture was a concentrated concern with the point-present, the nearby and the small. The gods of Classical man were little more than human beings drawn in the large. His mathematics was the visible space geometry of Euclid. The architecture, as expressed in the Doric Temple, was wholly oriented to the external view, with its rows of columns and sculptured reliefs. The only interior was the simple cella, which was just large enough to house an heroic statue of a god or goddess, and which also faced to the exterior.

The primary art form of the Classical Culture was the free-standing nude statue of the human body. The typical nude statue was devoid of facial expression, designed deliberately to avoid revealing the personality of the original. Spengler points out that it was not until the late Roman period that human statues became at all biographical.

Classical painting, as revealed by the painted surfaces of the famous Greek amphorae or vases, was two-dimensional to a high degree, with almost no feeling of depth perception. "The Classical vase-painting and fresco—though the fact has never been remarked—has no time-of-day. No shadow indicates the state of the sun, no heaven shows the stars. There is neither morning nor evening, neither spring nor autumn, but pure timeless brightness." The human figures are highly stylized representations of warriors, maidens and satyrs. After studying a group of these vases, it is startling suddenly to come upon a Hellenistic portrait painting of the 1st Century A.D. and to realize that one is in a new world of art. Here one sees a portrait that is truly biographical, revealing clearly the personality and character of the original.

According to Spengler, Classical man was ahistorical, or lacking in any sense of or feeling for history. He could write brilliant accounts of contemporary events, such as Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, or Xenophon's Anabasis, but anything of the remote past became transformed into myths, such as the Homeric legends. He had little appreciation of the reckoning of time and did not create an adequate calendar until the time of Julius Caesar. Classical man would have had no understanding whatsoever of our present day interest in archaeology. Thus, when the Acropolis was rebuilt after the Persian invasion of Xerxes, the Athenian citizens merely threw the remains of the former structures over the side of the hill into a massive dump heap.

The outstanding literary form of the Classical Culture was the drama, as exemplified in the great tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. These dramas were all, according to Spengler, "situation" tragedies, in which the protagonists were led to their destruction, not by their own deeds, but by the action of blind fate. Typical is the familiar story of Oedipus, which is not the tale of a hero struggling against alien forces and his own internal demons but one of a man who is led to his destruction by blind forces which he cannot attempt to combat.

An important feature of the Attic drama was its extreme formalism. Spengler points out that this effect was achieved deliberately in many different ways. In addition to the emphasis upon the so-called dramatic unities, the Greeks introduced the device of the chorus which largely dominated every scene. Masks, stilt-like shoes and padded clothing all combined to eliminate any possibility of individual characterization. This effect was further enhanced by monotonous sing-song speech delivered through a mouthpiece fixed in the mask. The result, according to Spengler, was exactly in keeping with the Attic spirit which prohibited all likeness-statuary.

The characteristic form of political organization of the Classical Culture was the Polis, or city-state-again an exemplification of the small and near. Instead of extending their frontiers by means of lateral expansion, Classical men established overseas colonies through maritime excursions. These colonies in turn became separate city-states, only loosely affiliated with the mother-city. This form of political organization was maintained rigorously throughout the Classical world and was only broken down by the emergence of the Roman Empire. Undoubtedly this spirit of separatism and exclusiveness was an important factor in causing the never-ending warfare amongst these small states.

We turn now to a consideration of our West European, or Faustian Culture. Here we find a soul which is diametrically different from that of the Classical. Spengler calls it one of the great paradoxes of history that Faustian man should have developed such a cult of worship of the Classical Culture, which is so alien to him and which he has never really understood.

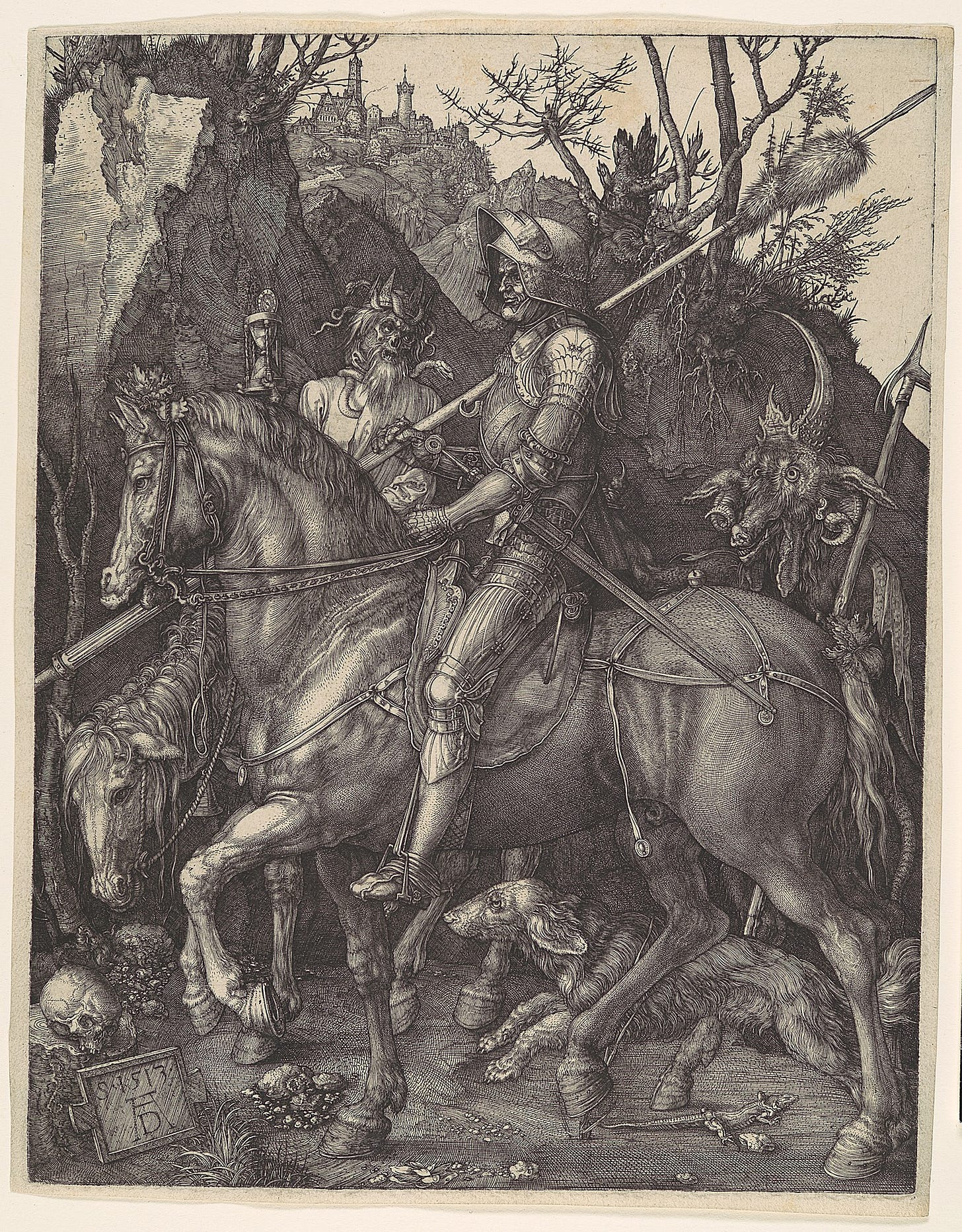

The prime symbol of the Faustian Culture is a limitless will-to-power and a reaching out into infinite space. Faustian man is as dynamic as Classical man was static, and every aspect of our Culture is an expression of this dynamism. Out of the forms and symbols of Christianity, Faustian man created a new religion of his own, with Mary, the Mother of God, superseding Jesus as his principal deity. Spengler sees in Mary a symbol of care and of the Faustian feeling for time and history. As the Culture developed, the image of God, the Father, became more and more ethereal until it was almost identical with that of infinite space itself.

A counterpart to the adoration of Mary as the Queen of Heaven was an equally fervent belief in the constant nearby presence of the Devil and his cohorts. Spengler describes this duality as one of the most essential elements of the Gothic spirit and one which modern man is no longer capable of understanding. On the one hand, Gothic man saw Mary as a figure of utter beauty and tenderness, while, on the other, he felt himself surrounded by the realm of the Devil with his army of goblins, night-spirits, witches, werewolves, all in human shape. Spengler maintains that these two concepts were believed with a depth of sincerity that it is not possible to exaggerate, and that disbelief in either was deadly sin. “Man walked continuously on the thin crust of the bottomless pit. Life in this world is a ceaseless and desperate contest with the Devil, into which every individual plunges as a member of the church militant, to do battle for himself and to win his knight’s spurs.”

In contrast to the static geometry of Euclid, the Faustian Culture produced the calculus, which is essentially the mathematics of motion. Spengler describes Faustian mathematics as dealing with functions and functional analysis rather than with concrete numbers. The creation of non-Euclidean geometries represented another step away from the Classical feeling for numbers. The culminating development, however, was the idea of multi-dimensional space which in turn led to the theory of Relativity.

The scientific interest of Classical man was almost wholly speculative, with little interest in experimentation and none whatsoever in technology. Faustian man, on the other hand, tested his scientific theories with experiments, and through these methods, developed a technology that was destined to overwhelm the whole world.

In architecture, the perfect expression of the Faustian spirit is the Gothic cathedral. As the Greek temple is wholly exterior, the Gothic cathedral can be appreciated only when viewed from within. The straining upward thrust of the mighty columns and pointed arches, the huge windows of coloured glass which impart to the outside light an ethereal quality, all combine to give one a feeling of reaching out into infinite space.

Although there have been many outstanding sculptors in our Culture, the material (with which the sculptor is forced to work) is too intractable to serve as an adequate vehicle to express the far ranging Faustian soul. Much better suited is portrait painting which is not only biographical but also in its emphasis on depth perspective gives the impression of infinite space. But greatest of all the arts as an expression of the Faustian spirit is music, which transcends all temporal and spatial barriers and lifts man out of himself into the infinite.

The typical literary form of the Faustian Culture is the biography, either as the story of the life of an actual individual, or in the more popular form of the novel which developed later out of the biography. In either case we find a story, dynamic in character, of the development of individual human beings and of their struggles with forces outside of themselves as well as with demons within their own natures.

In drama Faustian man created a form of grand tragedy which was very different in character from the "situation" tragedies of the Classical world. In Shakespeare's Macbeth and Goethe's Faust we are dealing with individuals who display a limitless will-to-power, and who are led to their destruction, not by blind fate, but by their own deeds. "It is Time that is the tragic, and it is by the meaning that it intuitively attaches to Time that one culture is differentiated from another; and consequently "tragedy" of the grand order has only developed in the Culture that has most passionately affirmed (the Faustian), and that which has most passionately denied (the Classical), Time."

Faustian man is historically minded to an extreme degree. His precise reckoning of time for centuries and millennia of the past, his invention of the clock in the 11th Century, his passion for archeology, are all facets of the same spirit. Spengler saw a close relationship between the dynamic quality of the Faustian Culture and the historical spirit and asserted that to describe it as a dynamic culture is only another way of emphasizing the eminently historical character of its soul.

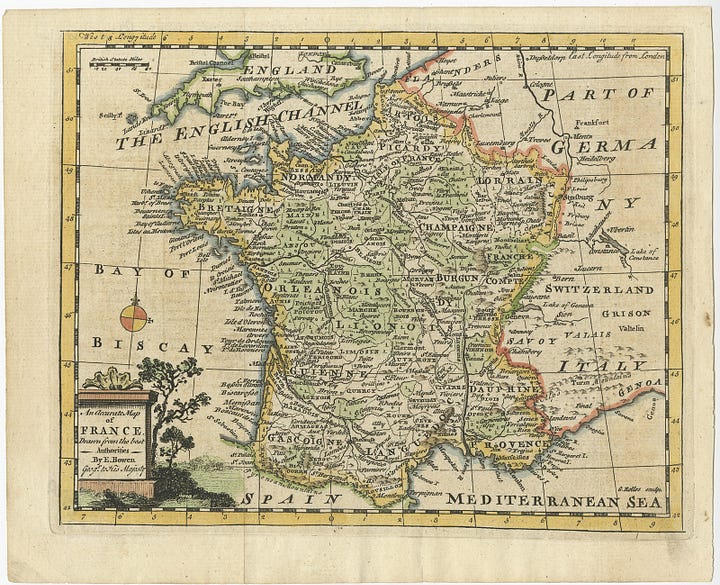

The characteristic form of political organization of the Faustian Culture is the nation state extending over a wide geographical area. Also, according to Spengler, the characteristic form of government is the dynastic monarchy. The Faustian feeling for time and care leads naturally to a strong desire for continuity and even perpetuation insofar as possible of the ruling family. The passionate devotion, almost a religion in itself, which Faustian man feels for his Fatherland, is a characteristic symbol of our Culture.

Spengler sees in parliamentarism and democracy merely a transitional stage between the dynastic monarchy and the coming of the Caesars. Where democracy becomes complete it lapses quickly into tyranny, as in the case of France in the last decades of the 18th Century. Parliamentarism works as an effective system of government only in those rare cases such as in Great Britain in 18th and 19th Centuries, where a powerful aristocracy manages, under the forms of democracy, to retain the control of government within its firm grasp. Even in the British example, however, Spengler sees clear signs of decay of parliamentarism by the end of the 19th Century.

When we turn to the Arabian or Magian Culture we find ourselves confronted by a culture that is not only different in form but also radically different in concept from all the others. The idea of a Magian Culture is the unique creation of Spengler himself. It is the outgrowth of the fact that there flowered in Asia Minor around the beginning of our Christian era a group of monotheistic religions which, though differing in dogma, had a common religiosity and a common world outlook. They are all the end results of several centuries of the teaching of prophets such as Amos, Isiah, Jeremiah and Zarathurstra.

Spengler saw in these prophetic teachings the birth of the Magian soul. Each of the prophets taught a belief in one god—Yahweh, Ahuremazda or Murduk-Baa—who represented the principle of good and all other deities being either impotent or evil. Along with this doctrine there arose the hope of a Messiah, first in the teaching of Isaiah, and then appearing everywhere during the next few centuries. This is the essence of the Magian religion, containing the idea of the historical struggle between good and evil in which the power of the good finally triumphs on the Day of Judgment. This moralization of history was basic in the religions of the Persians, the Chaldees and the Jews.

In its prime symbol, the Magian Culture emphasizes the cavern-like character of its world. “The world of Magian mankind is filled with a fairy-tale feeling. Devils and evil spirits threaten man; angels and fairies protect him. There are amulets and talismans, mysterious lands, cities, buildings, and beings, secret letters, Solomon’s seal, the Philosophers’ stone, and over all this poured the quivering cavern-light that the spectral darkness ever threatens to swallow up.”

This unceasing struggle between the forces of good and evil, with man as the center of the drama, permeates all aspects of the Magian Culture. There is something magical in algebra, a prime creation of Magian man, with its indefinite numbers and unknown quantities. Also essentially Magian is the Ptolemaic picture of the universe, with the earth at its center and surrounded by the cavern-like dome of the heavens.

Not only is Magian man's feeling for space radically different from that of the Classical or Faustian, but equally different is his feeling for time. Thus, Magian man was convinced that everything has a definite "time" from the origins of the Messiah, the hour of whose coming was set down in the ancient texts to the minor events of everyday life. Out of this belief emerged the early Magian astrology which assumes that all things are written down in the stars and that it is possible to foretell the course of human events by scientific calculations of the course of the planets.

In architecture, the closed-in space of the basilica and mosque is the perfect expression of the cavern-feeling: "Where the Egyptian puts reliefs that with their flat planes studiously avoid any foreshortening suggestive of lateral depth, where the Gothic architects put their pictures of glass to draw in the world of space without, the Magian clothes his walls with sparkling, predominantly golden, mosaics and arabesques and drowns his cavern in that unreal, fairy-tale light which for northerners is always so seductive in Moorish art."

Most fundamental of all to the Magian world outlook is the conception of the state. In contrast to the Faustian idea of a fatherland, Magian man had no earthly home with a definite geographical location and clear-cut frontiers. Instead, he created the idea of the consensus, a nation of true believers in a particular religious faith no matter where they might be located geographically. This idea, so alien to western man, is expressed in the words of Jesus; “Wherever two or three are gathered together in my name, there will I be also.”

The government of this Magian nation was also unique. In it the notion of a separation of the church and the state was unthinkable. The law of Magian nations is a law of creed-communities. In contrast to the laws of Classical and Faustian man which arose from practical experience, Magian man believed that all laws came directly from God who revealed them first to certain enlightened individuals. Such individuals in turn find the truth, not by personal pondering, but by ascertaining the general conviction of their associates which cannot err because the mind of God and the mind of the community are the same. If a consensus is found, truth is established.

According to Spengler, this idea of the consensus, unbounded by national frontiers, still permeates the Jewish race of today and accounts for the characteristic internationalism of this people. To Faustian man, with his deep-seated feeling for a fatherland, for which he is willing to fight and die, the idea of the consensus is utterly alien and incomprehensible.

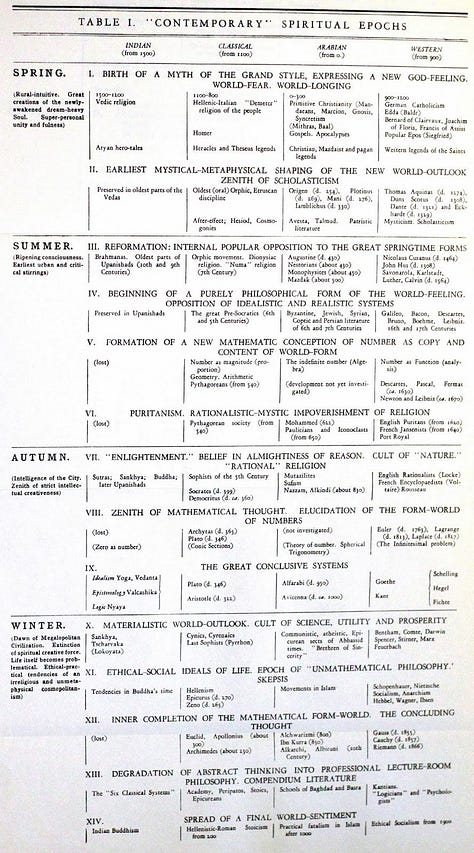

Having covered in an abbreviated form the world outlook of three leading cultures, we turn now to a consideration of the life-cycles of these same cultures. Spengler dates the cultural, or living phase, of the Classical organism from about 1100 B.C. to about 100 B.C. The Magian Culture extends from the birth of Christ to about 1000 A.D. and the Faustian from about 900 A.D. to about 1900 A.D.

Spengler asserts that the pre-cultural man had no history in any proper meaning of that word. Such primitive people led a tribal and plant-like existence with an endless and meaningless repetition of births, struggles and death. The only important contribution of pre-cultural men, in Spengler’s view, was the creation of a group of mighty legends and sagas which were the harbingers of the later births of several cultures. Thus, the Classical Culture had its Homeric legends, the Faustian its Nibelungenlied and Viking sagas, and the Magian the utterances of its line of great prophets.

In studying the history of several high cultures it is essential to keep in mind three basic Spenglerian concepts. First, it is necessary to realize the unity of all developments that unfold themselves in the life of each separate culture. At the core of the Spenglerian philosophy of history is the belief that the expression-forms of all branches of a culture are bound together in a tight morphological relationship. Thus, the religion, the mathematics, the architecture, the art forms, the philosophies, dramas and poetry, even the craftsmanship and choice of materials, are all expression-forms of the prime symbol of each separate culture. To understand fully the form-problems of history one must be aware of the unique character of such developments in each culture and of their close mutual relationships.

The second concept is that each important stage in the youth, maturity and decay of each culture lasts for the same period of time as the similar stages in all of the other high cultures.

The third and final concept follows from the second. It is the idea that every important stage in the life of a culture is contemporaneous with a comparable period in all the other cultures. Thus, Spengler uses the word "contemporaneous" to mean, not the same date in a chronological calendar, but as referring to an event or stage in the development or decay of a culture which has its counterparts in similar periods in the life-cycles of all the other cultures.

Although the birth of a culture occurs in the pre-urban country-side, its history is largely one of the gradual urbanization of society. Thus, the developments of art and intellect are for the most part products of the cities. In the early stages of a culture this trend represents a normal and healthy growth. It is only in the late stages, when a culture has exhausted its potential for creativity, that one can see the sickness of society produced by the materialism of the giant cities of a dawning civilization which progressively drains all vitality from the surrounding country-side.

During the youth of a culture, two principal estates emerge—that of the nobility and that of the priesthood. The former are the fact men, the doers and the warriors, who act largely from a sure instinct. The priests, on the other hand, are the rationalizers and systematizers of life. In the Faustian Culture these two estates have engaged in a constant struggle with one another. It is, in Spengler's view, the fundamental conflict between the world-as-history represented by the nobility, and the world-as-nature represented by the priesthood. Initially, this conflict is presented as a broad generalization as though it applied to all the cultures. Later Spengler makes clear that the situation he describes is applicable only to the Faustian Culture and that similar conflicts between the two estates did not appear in either the Classical or the Magian Culture.

The first great intellectual creations of a culture are the work of the priesthood. Such creations are known to us today as works of scholasticism and represent an attempt to rationalize the early religious beliefs. In the Faustian world this development culminated in the Summa Theologia of Thomas Aquinas, in which the author undertook to reduce the conduct of life to an exact science. His objective was the salvation of souls, and to this end he laid down rules of conduct based upon the Laws of God exactly as a modern scientist bases his conclusions upon the Laws of Nature. This intellectual structure dominated the thinking of the early Faustian Culture, and was only broken down by the emerging skepticism of the early lay scientists of the 16th and 17th Centuries.

In the Magian Culture, a comparable development is seen in the writings of the early church Fathers. This movement culminated in the Civitas Dei of St. Augustine, whom Spengler describes as "the last great thinker of Arabian Scholasticism, anything but a western intellect." Because Augustine was purely Magian in his world outlook, his writings have always been a thorn in the flesh of western theologians who have struggled to reconcile his thinking with their own.

In the old age of a culture, as the importance of the lay philosopher and scientist increases, and that of the priest diminishes, the latter is absorbed into a larger group of intellectuals in which the philosopher and the scientist play the leading roles. The importance of the nobility is similarly reduced and the nobles, as the fact men, are largely replaced by the entrepreneurs of business, and, to a lesser extent, by professional military leaders.

Spengler considers the peasantry as a non-estate. The plant-like existence of the peasants, with their close ties to the soil and the recurring cycles of weather, births and deaths, prevent them from taking any active part in the life of a culture. In the later stages of a culture, however, there emerges, in the city-dwellers or burghers, a third estate which grows steadily in importance as the culture matures and finally dominates the life of society. It is this class that carries through to fulfillment the various expression forms of a culture and leads in the transition from the cultural to the civilization stage of life.

A vital turning point in the life of a culture is the religious reformation which occurs contemporaneously in a fairly late phase of the life of every culture. In each case it is an effort to restore the religion to the purity of its original idea. For the Faustian world the reformation was largely the intellectual work of Luther and Calvin, and its most important outcome was the Puritanical Movement of Cromwell and his followers in England and Scotland. In the Classical Culture the reformation was led by Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans of the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. The Pythagorean revolt was fundamentally an effort to break away from the Olympian Pantheon of gods and to restore the early and simple worship of Demeter, the Earth Goddess. It was also a Puritanical Movement and led amongst other things, to the destruction of Sybaris, the city of "all evil" in Italy.

In the case of Magian man, however, the reformation was nothing less than the emergence of Mohammed and the rise of Islam in the seventh century A.D. Spengler refuses to admit that Mohammedanism was a separate and distinct religion. “At most Islam was a new religion only to the same extent as Lutheranism was one. Actually, it was the prolongation of the great early religions. Equally, its expansion was not (as is even now imagined) a migration of peoples: proceeding from the Arabian Peninsula, but an onslaught of enthusiastic believers, which like an avalanche bore along with it Christians, Jews, and Mazdaists and set them at once in its front rank as fanatical Moslems. It was Berbers from the homeland of St. Augustine who conquered Spain, and Persians from Irak who drove on to the Oxus. The enemy of yesterday became the front-rank comrade of tomorrow. . . . The soul of the Magian Culture found at last its true expression in Islam.”

In all cases, Puritanism displayed a sober, pedantic kind of fanaticism, from which all the joy and humor of the early springtime religions had disappeared. In the Faustian world every Puritan, having become his own priest, carried within him his own personal Hell, as was vividly shown in Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Similar sobriety and earnestness were shown in the ranks of the Pythagoreans and in the armies of the early Caliphs.

Puritanism was chiefly a movement of the urban middle class and was generally opposed by the nobility. With its urban background of the Puritan movement contained the seeds of rationalism which, after the passage of a few generations, burst forth everywhere. Puritanism was thus the prelude to the Age of Enlightenment. Locke in England, Voltaire in France, and Kant in Germany were the philosphic leaders of this development. In the Classical world, a similar movement unfolded under the aegis of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.

The 18th Century in Europe also witnessed a softening of the harsh fanaticism of the Puritan as a result of the emergence of the so-called Pietistic faiths, such as those of the Methodists and the Quakers. Under the growing influence of scientific materialism, there appeared concurrently the idea of god, the great watchmaker, who was believed to have started the machinery running and then to have left it to its own devices. In the Magian world the comparable and contemporaneous development of Pietism was known as Sufism.

In Spengler's view the principal art forms of the Faustian world reached their culmination in the 18th Century—the rococo in architecture, and the great contrapuntal creations of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven in music. He believed, however, that portrait painting had reached its apogee in the 17th Century with the work of Rembrandt. Western science, on the other hand, continued its free-wheeling advance throughout the 19th Century and, according to Spengler, only completed its basic thought structure in the early 20th Century.

In the Classical world, the work of Phidias and Praxiteles in Athens during the 5th Century B.C. marked the culmination of the art forms of this Culture. Classical science was largely speculative and the end term of this development is found in Archimedes.

A basic aspect of the transition of a culture to a civilization is the growing dominance of money and the rise of a class of capitalists and business entrepreneurs. In the Faustian world the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the later 18th Century, accompanied by the philosophy of David Hume and Adam Smith, marked the emergence of the power of money.

When we turn to the Classical world, our scene shifts from Greece to Rome. Spengler asserts that a study of economics had no place in the small-scale life of the Greek cities. The history of Rome, however, is incomprehensible unless viewed from an economic standpoint. After the end of the second Punic War in the 3rd Century, B.C., there emerged in Rome a new class of capitalists that became more and more dominant during the following two centuries and culminated in such figures as SuIla, Pompey and Crassus. These men were the leaders in the unceasing warfare, chiefly civil conflicts, that took place during this period.

In a later chapter the difference in the concepts of Classical money and Faustian money is discussed in some detail. At this point it must suffice to point out that the Roman idea of wealth was a mass of concrete objects, such as gold and slaves. For late Faustian man, on the other hand, wealth arose out of credit or functional money created by the dynamism of business entrepreneurs.

According to Spengler, the power of money remains dominant during the early stages of a civilization but finally succumbs to what he terms the power of blood with the coming of the Age of the Caesars. Thus, with the arrival of Julius Caesar and Augustus, the power of money was reduced to a subordinate role. It was the great capitalists of Rome who were responsible for the murder of Julius Caesar because they saw in him the beginning of the end of their power. In the Faustian world, however, we are still completely in the grip of a money economy.

Another important aspect of every late culture is the geographical expansion of its power and influence. For the Magian world, as we have already seen, this phenomenon appeared in the tidal waves of Islam which swept across north Africa into Spain and was finally checked by Charles Martel in southern France. Eastward the followers of Mohammed drove as far as the western borders of India.

The expansion of the more static Classical Culture was represented by a gradual extension of its power beyond the borders of the Mediterranean. This movement reached its limits in Spain in the west, England in the north, and Asia Minor in the east.

Most dramatic of all, however, has been the imperialistic expansion of the Faustian Culture. The early voyages of the Vikings were perhaps an early manifestation of this development. The real movement began, however, with the explorations of the Portuguese and Spanish navigators in the 15th Century and continued during the succeeding centuries with an ever rising tempo. Aided by improved navigational instruments and a vast superiority in military technology, Faustian man not only circumnavigated the globe, but also extended his power to its most remote corners.

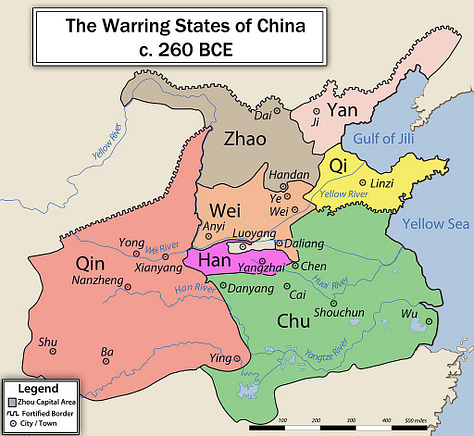

The first stage of a civilization is the period of “contending states.” This phrase is marked by a succession of frightful wars and usually lasts for a century or more. At the end of the period an agonized and exhausted world accepts gratefully the coming of the Caesars who unite the warring factions and bring about an era of peace and stability.

The period of contending states for the Classical world was mentioned above. Spengler sees the 19th Century as a period of transition from the Faustian Culture phase to that of civilization. The true civilization starts in the 20th Century with the holocausts of World Wars I and II. If Spengler's view is correct, we are now right in the middle of our period of contending states and still fairly far removed from our Age of the Caesars with its prospective haven of security.

Spengler considers Alexander of Macedon and Napoleon as contemporary figures. He asserts, however, that both were romantic adventurers whose conquests left no permanent mark. They appeared just prior to the emergence of the civilization stage and their empires vanished within short periods of time leaving scarcely a ripple on the surfaces of their respective worlds.

The megalopolis is a prime symbol of every civilization. These giant cities dominate the life of their worlds and drain the vitality of the surrounding country-side. In the Classical world Rome was the one true megalopolis. In the Magian, Alexandria and Constantinople were comparable centers of population. Spengler sees in London, Paris, Berlin and New York the giant cities of our own civilization.

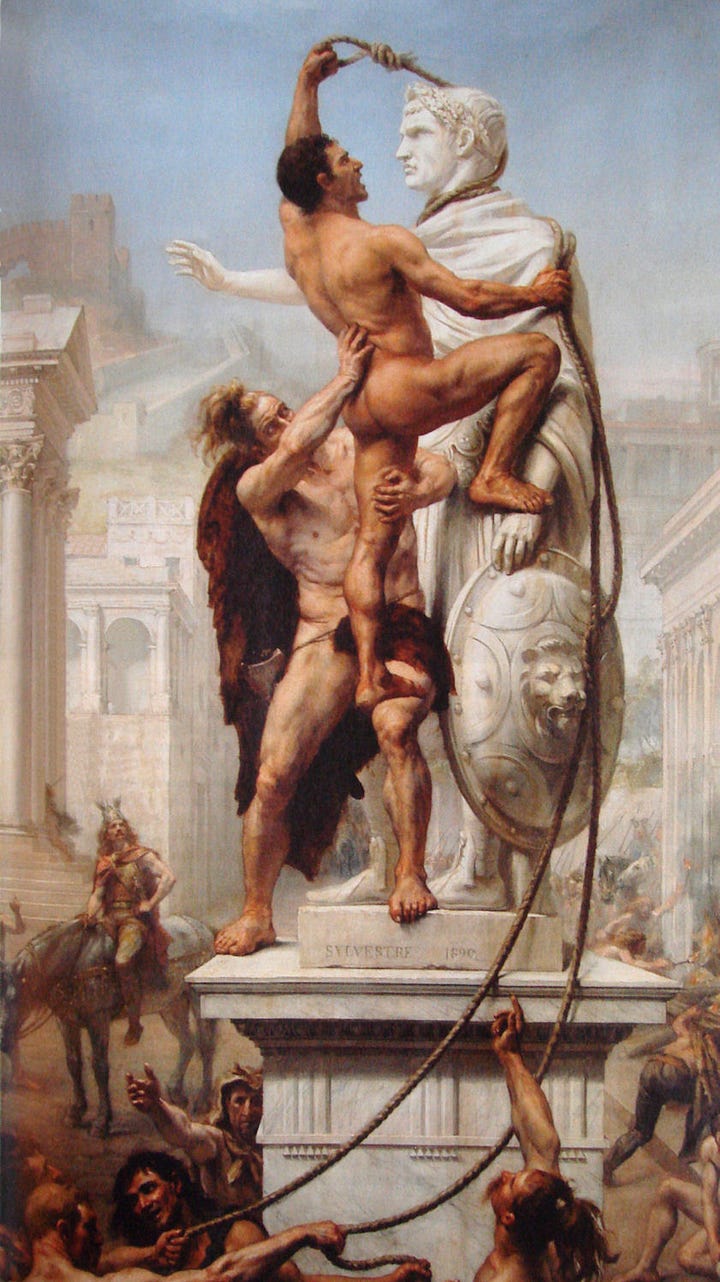

The inhabitants of the megalopolis are rootless, atheistic, and thoroughly materialistic. They erect giant structures, such as the Colosseum, the Pantheon, and the mighty Aqueducts of Rome, and the American skyscrapers of the Faustian world. All genuine creativity, however, has disappeared. In its place, a sucesion of schools and fads arise, flourish and quickly vanish.

An important characteristic of every megalopolis is the emergence of a new urban proletariat. In Rome this class consisted mainly of freed slaves as well as other immigrants from the outlying provinces. These people form a restless seething mass who are constantly threatening rebellion against the existing establishment. They are kept in check chiefly by liberal doses of Bread and Circuses, and by the modern equivalent in the form of welfare payments.

Another phenomenon of the late megalopolitan world is a gradual decline in population, despite a steady influx of fresh blood from outside. First, the nearby country-side is denuded of inhabitants by the magnetic attraction of the giant city. In these areas, agriculture practically disappears and food supplies are drawn from more and more remote sources. In the cities life continues to die out at the top. No longer is there pride in large families and in the succession of sons and heirs. This phenomenon is basically the result of a declining vitality of the urban population.

In the Classical civilization Stoicism was the dominant philosophy, a calm and static acceptance of the vicissitudes of life. Spengler sees in socialism the dominant and more dynamic philosophy of the Faustian civilization. He defines socialism more broadly than a mere belief in any particular political faith, or as a philosophy of human welfare. Instead, he sees it as an expression of the modern idea of “Progress,” and the Faustian will-to-power. He states that the stoic takes the world as he finds it, but that the socialist wants to recast it in form and substance, to fill it with his own spirit.

In every late civilization there appears what Spengler calls "a second religiousness." This is a pallid revival of a belief in the religious symbols of the early culture. He makes clear, however, that there is no connection between this development and such modern cults as Christian Science and Theosophy, for which he expresses nothing but scorn.

As pointed out earlier, a civilization may last on for a millennium or more as a result of sheer size or relative isolation; for example, China and India. On the other hand, a civilization may be destroyed almost overnight by a brutal invasion. Such was the case when the tiny army of Cortez struck down the Aztec-Mayan Civilization in Mexico. The Magian Civilization was overwhelmed by a series of invasions by barbarians from the steppes of Asia. This movement reached its culmination when all of Asia Minor was occupied by the Ottoman Turks, and Constantinople fell at last to the invader in 1453 A.D.

The collapse of the Roman Empire resulted from a combination of the barbarian within and the barbarian without. The decline in the population of Italy forced Rome to replenish the depleted ranks of her far-flung legions with recruits from the nomadic tribes which were pressing against her frontiers. Thus, the defense of the Classical world passed gradually into the hands of its enemies. From this point it was an inevitable step to the takeover of the almost empty shell of the Empire by the Goths, the Ostrogoths and the Germans.

According to Spengler, the peoples of a late or destroyed civilization revert to a historyless existence. Their struggles and the rise and fall of various groups have become meaningless for the great panorama of world history. During the period of contending states, they fought, bled and died for ideals and rights without which life seemed not worth living. After the coming of the Caesars, however, these goals ceased to have any meaning. “A hundred years more, and even the historians will no longer understand the old controversies.”

Spengler uses the word “Fellaheen” to designate the people of a late or collapsed civilization. It is a term of contempt which was first employed to describe the Egyptians of the post-Roman period. It means a people without vitality, direction or destiny.

This summary exposition of Spengler’s philosophy of history would not be complete without some comments on the literary organization of the work. A reader, on first approaching the Decline, is certain to be confused by the lack of any orderly presentation of the material. Thus, the author jumps abruptly from an opening chapter on mathematics to several chapters on his metaphysical assumptions, then back again to a discussion of the differences between cultures. Volume II opens with another lengthy metaphysical section, then moves into sections dealing with such diverse subjects as the megalopolis, the psuedomorphosis, the law, the religious reformations, the state, money and the machine, all presented without any apparently logical sequence. Throughout the whole work there is a constant turning back to the previously discussed subjects, with the author repeating and amplifying his earlier statements.

It is only after a reader has lived with the Decline for some time that he begins to realize that the work has an order and logic of its own and that the repetitions and back-trackings fit into a unique literary pattern that is more the nature of a musical composition than it is that of a straight exposition. H. Stuart Hughes, in his book on Spengler, expresses this point of view eloquently: “Hence even the back-trackings and repetitions play their part, indeed are nearly indispensable, in the tightly woven, all interrelated efect that the author seeks to convey. Actually the Decline can hardly be said to start and end at any particular point. It is not to be read as a logical sequence. It is rather—to use the language of music to which Spengler was so deeply attracted—a theme and variations, a complex, contrapuntal arrangement, in which no one idea necessarily follows another, but in which a group of ideas, whose mutual relationship is symbolically experienced rather than specifically understood, summon, answer, and balance one another in the sort of lofty, cosmic harmony that Goethe’s angels had proclaimed in the prologue and concluding stages of ‘Faust.’”

Very high quality, thank you.

I’m surprised this doesn’t have more engagement. A very nice summary of the ideas in the first few chapters. I’ve been reading Volume I the last few months. I’m taking my time to make sure I understand the content. John David Ebert’s summary videos have been a good resource to fill missing gaps and recontextualise parts. This article is a nice addition as well.